In the article below, Syracuse University historian Herbert Ruffin explores the rapid rise of the Black Lives Matter Movement in 2013 as the most recent development in the ongoing struggle for racial and social justice in the United States.

In the summer of 2013, three community organizers Alicia Garza, a domestic worker rights organizer in Oakland, California; Patrisse Cullors, an anti-police violence organizer in Los Angeles, California; and Opal Tometi, an immigration rights organizer in Phoenix, Arizona, founded the Black Lives Matter movement in cyberspace as a sociopolitical media forum, giving it the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter. The idea came when the three, who became aware of each other through Black Organizing for Leadership & Dignity (BOLD), a national organization that trains community organizers, all responded similarly to the July 2013 acquittal of neighborhood watch coordinator George Zimmerman by a Sanford, Florida, jury for the murder of seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin. Angered and deeply burdened by the verdict, members in BOLD social forums began asking the organization’s leaders how they were going respond to the assault on and devaluation of black lives. On July 13, 2013, Garza wrote a Facebook post which she titled “A Love Note to Black People” calling on them to “get active,” “get organized,” and “fight back.” For Garza, the injustice targeting black people was a disease called institutional racism that could not be defeated by just voting, being educated, and pulling oneself up with strapless boots. She ended by telling her readers that she loves them and that “Our Lives Matter, Black Lives Matter.” Cullors responded to the post with the hashtag “#BlackLivesMatter.” Tometi added her support and a new organization was born.

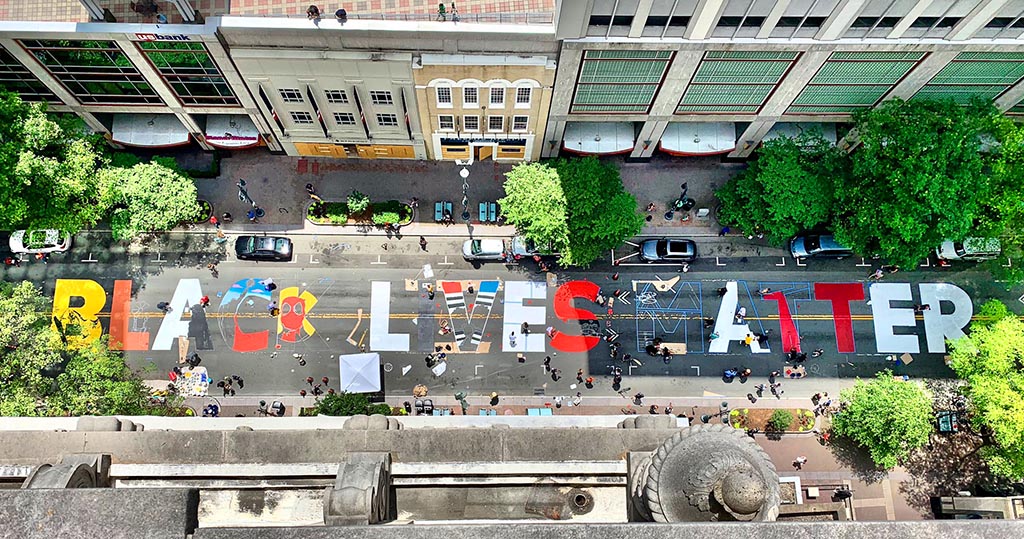

Photo by Ann Harkness (CC BY 2.0)

Black Lives Matter, like Dream Defenders in Daytona Beach, Florida, Million Hoodies Movement for Justice in Washington D.C., and Baltimore Bloc in Baltimore, Maryland, was one of many freedom rights groups formed during the protest for George Zimmerman’s arrest and trial. Unlike most other groups who organized courthouse demonstrations, Black Lives Matter immediately recognized the value of social media in developing a political agenda and mobilizing for action beyond petitioning for justice through mediums like Change.org. Using Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr, they created a movement unlike most black freedom campaigns that preceded them.

While Black Lives Matter drew inspiration from the 1960s civil rights/black power movement, the 1980s black feminist/womanist movement, the 1980s anti-apartheid/Pan African movement, the late-1980s political hip-hop movement, the 2000s LGBT movement, and the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement, they used newly developed social media to reach thousands of like-minded people across the nation quickly to create a black social justice movement that rejected the charismatic male-centered, top-down movement structure that had been the model for most previous efforts. Instead, like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the 1960s, Black Lives Matter engaged in collective planning for their campaigns. Unlike SNCC, but similar to Black Youth Project 100 in Chicago, Illinois, Black Lives Matter incorporated those on margins of traditional black freedom movements, including women, the working poor, the disabled, undocumented immigrants, atheists and agnostics, and those who identify as queer and transgender. These marginalized black people played visible and central roles in the formation of Black Lives Matter and in their ongoing community organizing and protests.

On August 9, 2014, Black Lives Matter members took their grievances to the streets for the first time through the Black Lives Matter Freedom Ride to Ferguson, Missouri. Here they participated in the non-violent demonstrations for justice in the wake of eighteen-year-old Michael Brown who had been murdered at the hand of police officer Darren Wilson. More than five hundred Black Lives Matter members from Baltimore, Maryland; Berkeley and Los Angeles, California; Boston, Massachusetts; Chicago, Illinois; Columbus, Ohio; Denver, Colorado; Detroit, Michigan; Houston, Texas; Nashville, Tennessee; New York City and Syracuse, New York; Portland, Oregon; Seattle, Washington; Tucson, Arizona; Washington D.C.; and Winston-Salem, North Carolina; descended on Ferguson. The number of cities represented reflected the rapid spread of the organization in just one year.

Like other protesters, Black Lives Matter members were angered not simply by the shooting of an unarmed African American but also because his body was allowed to lie in the street for four hours before it was eventually taken to the city morgue, an event that was well documented by bystanders with cell phones and distributed within minutes around the world via Twitter and Facebook. This instant exposure generated months of sometimes peaceful and sometimes violent protests which involved Ferguson residents at first but eventually drew tens of thousands of people from across the United States. The exposure of the protests and the police reaction to their chant, “Hands up! Don’t Shoot!” was literally broadcasted by thousands of on-the-scene protesters as well as by the traditional media, ensuring as never before, that the centuries-old issue of police brutality would now be addressed on the national and international stage.

Photo © Alex Garland

While Black Lives Matter was initially one of hundreds of organizations protesting in Ferguson, they eventually emerged as the one of the best organized and visible groups with their slogan “Black Lives Matter.” By autumn, that slogan had become the call for action against what many saw as the unjustifiable killing not just of Michael Brown but of dozens of other African American men and women whose deaths occurred away from the view of cell phone cameras. Moreover, with the creation of a webpage independent of corporate media control, their use of Twitter and Facebook to organize, and online conference calls to plan strategy, Black Lives Matter became a model for how black liberations groups in the twenty-first century can organize an effective freedom rights campaign.

The movement’s success also resulted from their inculcation of the feminist political mantra, the “personal is political.” That concept meant that each member’s personal experience is informed and molded by the various campaigns against systemic oppression that are inescapably political and collectively connected to the well-being of others. This framework has been used to transform Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s message, “None of us are free until all of us are free,” from a concept centered primarily on the freedom dreams of black heterosexual men to a campaign that equally addresses the freedom struggles of all people but is explicitly centered on black liberation. Dr. King’s message was central in the Black Lives Matter “State of the Black Union” statement released on January 22, 2015.

The effective melding of technology and womanist politics generated rapid organizational growth. By August 2015, the Black Lives Matter Movement had at least twenty-three chapters in the United States, Canada, and Ghana; with black people in London (UK), Paris (France), and in Africa and Latin America planning additional chapters. Growing international interest in the Black Lives Matter Movement stemmed from the April 18, 2015, police custody death of Freddie Gray of Baltimore, Maryland. Just as Black Lives Matter move from hashtag to the streets of Ferguson in 2014 had taken the movement to a new phase, the Baltimore rebellion of 2015 ignited a global movement where black cyber activists in Europe, Africa, the Caribbean, and Latin America drew inspiration from and modeled their efforts on both the Black Lives Matter and the 2010-2012 Arab Spring campaigns where North African and Middle Eastern women and young cyber activists toppled longstanding dictatorships in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen. Many of these young overseas activists called their efforts the “Black Spring” movement.

Between August 2014 and August 2015, Black Lives Matter chapters around the world have organized more than nine hundred and fifty protest demonstrations. Their call for social justice has ranged from targeting well-known police-involved deaths such as the Eric Garner strangulation in Staten Island, New York, on July 17, 2014, and lesser known cases involving the killing of homosexual and heterosexual black women and children such as twelve-year-old Tamir Rice in Cleveland on November 22, 2014. Partly as a result of the public outcry organized and promoted by Black Lives Matter, the U.S. Department of Justice has investigated police misconduct in several cities, including Albuquerque (New Mexico), Baltimore, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Ferguson, Newark (New Jersey), New Orleans (Louisiana), Portland, New York, North Charleston, Seattle, and St. Louis. On December 18, 2014, the U.S. Congress enacted the Death and Custody Reporting Act which now requires states receiving federal funds to document and report all deaths at the hands of police in local jurisdictions “that occur in the process of arrest.”

Despite these efforts, in the United States more black deaths directly or indirectly because of police violence ensured that the Black Lives Matter movement would continue to grow. On April 4, 2015, Walter L. Scott was shot in the back while fleeing from Officer Michael T. Slager, a policeman from North Charleston, South Carolina. On July 13, 2015, Sandra Bland was taken into custody near Prairie View University near Houston, Texas, after she was stopped by Brian Encinia, a Texas State trooper. She later died under mysterious circumstances in the Waller County Jail. On July 19, 2015, Samuel DuBose of Cincinnati, Ohio, was killed by Ray Tensing, a University of Cincinnati police officer during a traffic stop. Besides the race of each victim, all these incidents shared the rapid dissemination of video at the time of their encounters with law enforcement officers which led many viewers to question the tactics and in some cases the legality of police action. Black Lives Matter played a major role in alerting people about these incidents and spurring them to take action. As a consequence, millions of people are now aware of the ongoing impact of police brutality on black lives.

Photo by Fibonacci Blue (CC BY 2.0)

On November 28, 2014, Black Lives Matter adopted a new protest tactic that soon gained national attention. On that day, Black Lives Matter activists joined with other grassroots organizations like Oakland’s BlackOutCollective to disrupt successfully holiday season shopping in San Francisco-Bay Area malls and Walmart stores. Similar disruptions occurred in Boston, Chicago, Memphis, New York, Seattle, and Washington, D.C. These organizations used the busiest shopping day of the year to remind shoppers and larger communities that the issues of police brutality, access to proper health care, housing discrimination, poor education, immigration reform, racial disparities in median wealth, and the prison industrial complex had to be addressed by the entire nation. These demonstrations, as with all Black Lives Matter protests, were intentionally provocative in order to draw attention to issues that were continually ignored by most non-black people.

The movement’s influence reached the national popular entertainment media for the first time in February 2015 when some Black Lives Matter members made an appearance in a Law & Order: SVU episode protesting a Paula Deen-like character who murdered an unarmed black teenager who “fit the description” of a serial rapist. In the same month, Essence magazine became the first major black American publication to profile the movement. The cover of Essence on the magazine’s forty-fifth anniversary issue featured a black-only background with grey text that read “Black Lives Matter: What We Must Do Now.” The magazine cover and the lead story of Black Lives Matter advanced the idea that Black Lives Matter is at the heart of a new black freedom movement that includes all who have been ignored or marginalized in earlier freedom campaigns. As if to symbolize its rise as a new generation of activists with a broader, more inclusive view of freedom, Black Lives Matter selected Kendrick Lamar’s song “Alright” as the closing theme of its first national conference held in Cleveland, Ohio, in July 2015, precisely because it is socially conscious hip-hop.

By the summer of 2015, Black Lives Matter had initiated another new tactic, publicly challenging politicians, including 2016 presidential candidates, to state their positions on Black Lives Matter issues and how their policies will lead to the improvement of black communities. Recognizing that virtually all non-black politicians (and many non-black Americans) failed to fully acknowledge the historical and contemporary impact of slavery as well as ongoing discrimination against persons of African descent, they challenged liberal and conservative candidates to speak about the issues that most concerned black voters and affected black lives.

On July 18, Black Lives Matter members disrupted the NetRoots national annual convention of progressive cyber activists in Phoenix, Arizona. They publicly challenged Maryland’s former governor, Martin O’Malley, a candidate for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination, when he stated “All lives matter.” He quickly retracted his words after Black Lives Matter activists persuaded him that statements like that, while appearing innocent and fair, in fact marginalize the campaign to focus attention on the lives that all too often in this nation have not mattered—impoverished African Americans and other people of color.

On August 8, Black Lives Matter Movement activists disrupted and ultimately shut down a five-thousand-person rally in Seattle, Washington, where Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, another presidential candidate, was slated to speak. In both of these incidents, Black Lives Matter activists claimed that the liberal supporters of O’Malley, Sanders, and other presidential hopefuls had remained silent on police brutality and other issues facing African Americans, even as they called for black voters to support their candidates. This silence prompted Black Lives Matter on August 9 to announce that it would not endorse any presidential candidate, nor would it affiliate with a political party. This position has provided Black Lives Matter activists the latitude to pressure policymakers, including President Barack Obama, for policy reforms such as for the inclusion of African American girls in his “My Brother’s Keeper” initiative, a position adopted from the African American Policy Forum, “Black Girls Matter.”

Courtesy Office of Congresswoman Alma S. Adams

While many Americans have criticized Black Lives Matter for sabotaging itself, their protests are helping the Democratic Party to take black issues and black voters more seriously. As a consequence, most major Democratic presidential candidates are developing new social policy agendas that specifically address policing reform and racially disproportionate incarceration. Ironically, Dr. Ben Carson, the only African American competing for the Republican presidential nomination, regularly criticized the Black Lives Matter Movement, an action that he felt would appeal to his conservative, mostly white supporters. Carson’s tactic was increasingly used after July 2015 by other GOP presidential candidates, including Donald Trump, Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, and Jeb Bush. Other GOP candidates like Chris Christie and Rand Paul have been pressured into pushing for legislative reforms by social groups that work as coalition partners with Black Lives Matter. These reforms include addressing job application discrimination and prison sentencing.

The Black Lives Matter Movement has been successful in creating a new mechanism for non-violently addressing racial inequality in twenty-first century America. Its organizational structure builds on the legacy of earlier reform campaigns, including the civil rights/black power movement, Pan Africanism, Africana womanism, the LGBT movement, and the Occupy Wall Street movement while using cyber activism to promote its agenda. Specifically, Black Lives Matter puts the feminist theory of “intersectionality” into action by calling for a united focus on issues of race, class, gender, nationality, sexuality, disability, and state-sponsored violence. It argues that to prioritize one social issue over another issue will ultimately lead to failure in the global struggle for civil and human rights.

Black Lives Matter continued to lead protests against police abuse and anti-racism rallies across the nation between 2016 and early 2020 mainly because police and vigilante shootings of unarmed black people continued during those years, with at least 30 individuals added to the list of victims. Coverage of these incidents by major media outlets declined dramatically, however, partly due to the election of Donald Trump as President in November 2016. The new administration quickly signaled that its sympathies lay with the police and especially with harsh police tactics.

Then three incidents in the first months of 2020, the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery near Brunswick, Georgia on February 23, Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky on March 13, and George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on May 25, brought before the nation the continuing problem of police and vigilante murder which this time generated huge protests and in the process made the Black Lives Matter Movement more influential than ever before.

The Floyd murder on Memorial Day was especially shocking because a videotape of the incident showed a policeman’s knee on Floyd’s neck as he cried out “I can’t breathe” numerous times before he died. That incident almost immediately generated protests that continue into mid-July, 2020. By conservative estimates these protests have involved more than 20 million Americans in 2,000 cities and towns in every state in the United States. Similar protests took place in more than 60 nations on every continent except Antarctica despite the ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic. The magnitude of these protests and the support of BLM efforts by the majority of Americans for the first time, prompted police reforms in dozens of cities as well as state and national legislation calling for changes in police tactics and behavior. Additionally the protests have initiated a nationwide examination of racial injustice far beyond the issues of police and vigilante violence. While the extend and results of these changes remain to be measured, there is no doubt that the Black Lives Matter movement has been the major catalyst for these developments.