Antebellum African Americans took enormous pride in Haiti. The nation of the enslaved rose in rebellion in 1791 and on January 1, 1804 won its independence from France. At that moment the Republic of Haiti was born as the first black republic in the world, the first independent country in Latin America, the second independent nation in the hemisphere, after the United States.

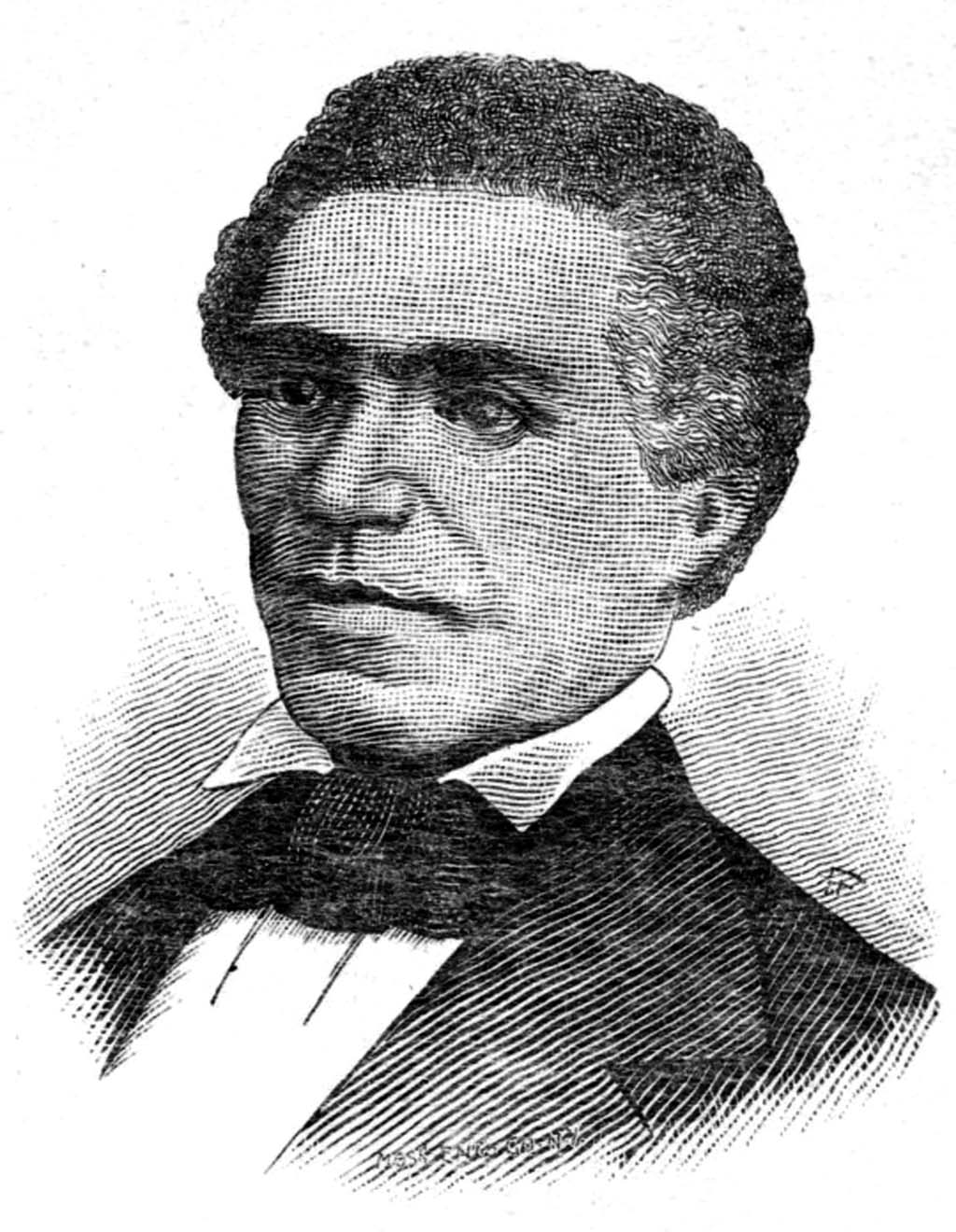

Twenty two years later John Browne Russwurm, the second black college graduate in the United States chose the Haitian Revolution and the future of the nation as the subject of his commencement address at Bowdoin College in Brunswick Maine, on September 6, 1826. Russwurm was born in Port Antonio, Jamaica, October 1, 1799, of a black mother and a white father who was an English merchant in the West Indies. At the age of eight, Russwurm was sent to school in Quebec. When the elder Russwurm moved into the District of Maine a few years later, he brought his son with him. Russwurm entered Bowdoin College in the fall of 1824 and graduated in 1826. Six months later in March 1827, he became coeditor and copublisher with Samuel B. Cornish of Freedom’s Journal, the first black newspaper published in the United States. But Russwurm, convinced that racism prevented African Americans from full citizenship and dignity, became an emigrationist. In 1829 Russwurm became the superintendent of public schools in Liberia which was then under the control of the American Colonization Society but which became with independence in 1847, the second black republic in the world. In 1836 he was appointed governor of the Cape Palmas district of Liberia, and he continued in his position until his death on June 17, 1851. The full text of Russwurm’s speech is presented here with the permission of the Bowdoin College Archives, where the original is kept.

The changes which take place in the affairs of this world show the instability of sublunary things. Empires rise and fall, flourish and decay. Knowledge follows revolutions and travels over the globe. Man alone remains the same being, whether placed under the torrid suns of Africa or in the more congenial temperate zone. A principle of liberty is implanted in his breast, and all efforts to stifle it are as fruitless as would be the attempt to extinguish the fires of Etna.

It is in the irresistible course of events that all men who have been deprived of their liberty shall recover this precious portion of their indefeasible inheritance. It is in vain to stem the current; degraded man will rise in his native majesty and claim his rights. They may be withheld from him now, but the day will arrive when they must be surrendered.

Among the many interesting events of the present day, and illustrative of this, the Revolution in Haiti holds a conspicuous place. The former political condition of Haiti we all doubtless know. After years of sanguinary struggle for freedom and a political existence, the Haitians on the auspicious day of January first, 1804, declared themselves a free and independent nation. Nothing can ever induce them to recede from this declaration. They know too well by their past misfortunes, by their wounds, which are yet bleeding, that security can be expected only from within themselves. Rather would they devote themselves to death than return to their former condition.

Can we conceive of anything which can cheer the desponding spirit, can reanimate and stimulate it to put everything to the hazard? Liberty can do this. Such were its effects upon the Haitians—men who in slavery showed neither spirit nor genius: but when Liberty, when once Freedom struck their astonished ears, they became new creatures, stepped forth as men, and showed to the world, that though slavery may benumb, it cannot entirely destroy our faculties. Such men were Toussaint L’Ouverture, Desalines and Christophe!

The Haitians have adopted the republican form of government; and so firmly it is established that n no country are the rights and privileges of citizens and foreigners more respected, and crimes less frequent. They are a brave and generous people. If cruelties were inflicted during the revolutionary war, it was owing to the policy pursued by the French commanders, which compelled them to use retaliatory measures. For who shall expostulate with men who have been hunted with bloodhounds, who have been threatened with and auto-de-fé, whose relations and friends have been hanged on gibbets before their eyes, have been sunk by hundreds in the sea—and tell them they ought to exercise kindness toward such mortal enemies? Remind me not of moral duties, of meekness and generosity. Show me the man who has exercised them under these trials, and you point to one who is more than human. It is an undisputed fact, that more than sixteen thousand Haitians perished in the modes above specified. The cruelties inflicted by the French on the children of Haiti have exceeded the crimes of Cortes and Pizarro.

Thirty-two years of their independence, so gloriously achieved, have effected wonders. No longer are they the same people. They had faculties, yet were these faculties oppressed under the load of servitude and ignorance. With a countenance erect and fixed upon Heaven, they can now contemplate the works of divine munificence. Restored to the dignity of man to society, they have acquired a new existence; their powers have been developed; a career of glory and happiness unfolds itself before them.

The Haitian government has arisen in the neighborhood of European settlements. Do the public proceedings and detail of its government bespeak an inferiority? Their state papers are distinguished from those of many European courts only by their superior energy and nonexalted sentiments; and while the manners and politics of Boyer emulate those of his republican neighbors, the court of Christophe had almost as much foppery, almost as many lords and ladies of the bedchamber, and almost as great a proportion of stars and ribbons and gilded chariots as those of his brother potentates in any part of the world.

(Placed by divine providence amid circumstances more favorable than were their ancestors, the Haitians can more easily than they, make rapid strides in the career of civilization—they can demonstrate that although the God of nature may have given them a darker complexion, still they are men alike sensible to all the miseries of slavery and to all the blessings of freedom.)

May we not indulge in the pleasing hope, that the independence of Haiti has laid the foundation of an empire that will take rank with the nations of the earth—that a country, the local situation of which is favorable to trade and commercial enterprise, possessing a free and well-regulated government, which encourages the useful and liberal arts, a country containing an enterprising and growing population which is determined to live free or die gloriously will advance rapidly in all the arts of civilization.

We look forward with peculiar satisfaction to the period when, like Tyre of old, her vessels shall extend the fame of her riches and glory, to the remotest borders of the globe—to the time when Haiti treading in the footsteps of her republics, shall, like them, exhibit a picture of rapid and unprecedented advance in population, wealth and intelligence.