Reflecting on what we all witnessed last night during the Super Bowl Halftime Show, I kept recalling two scenes from Quentin Tarantino’s works: Pulp Fiction and Django Unchained. Of all movies, two movies by a white man who so frequently uses the “N” word in his works. There’s an iconic scene in Pulp Fiction where Samuel L. Jackson recites, “And I will strike down upon thee with great vengeance and furious anger.” The dialogue surrounding Kendrick’s performance during the Super Bowl Halftime Show last night, will probably be an ongoing dissection of Black culture, American ideology, identity, and the intentional satire of contextualizing your place in the world as a Black American.

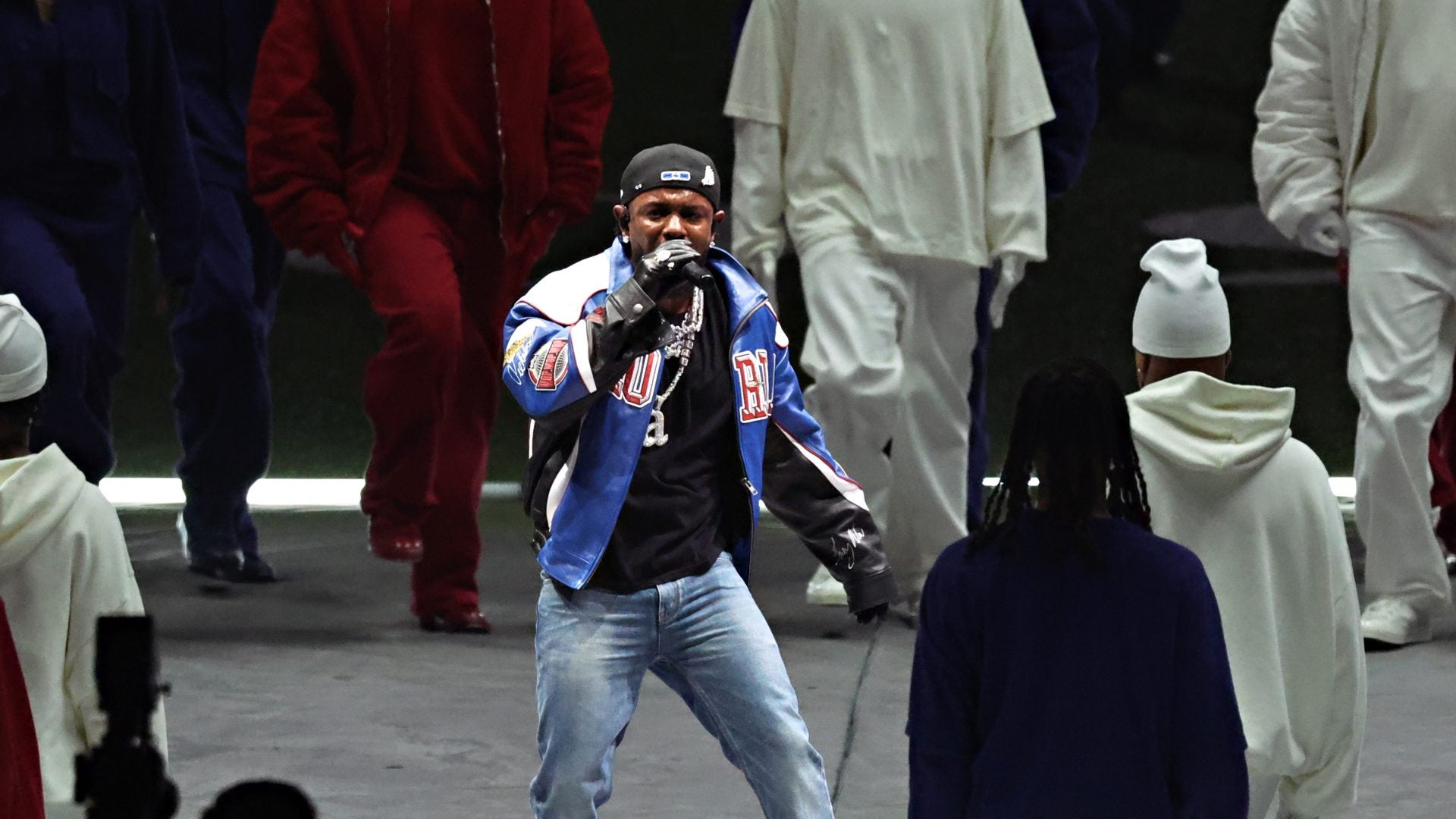

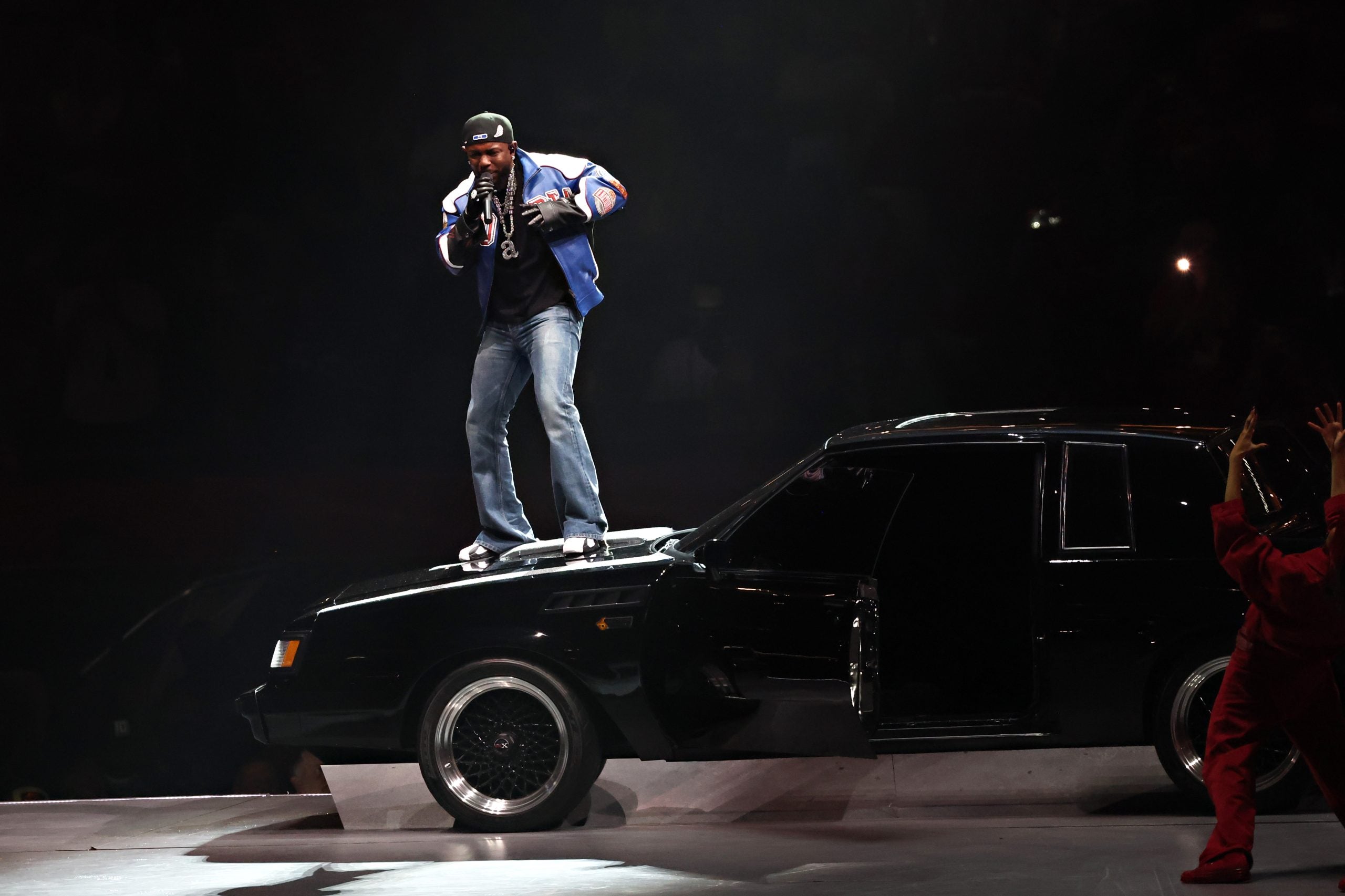

There’s the use of dancers (wearing blue, red, and white sets) morphing into various formations of the American flag, his Martine Rose jacket with Gloria (a reference to his “pen”) etched across the front, Samuel L. Jackson as Uncle Sam, a deconstructed GNX, and the set design of a prison yard or block of a street (depending on how you view it) in the middle of a PlayStation video game controller. The laced symbolism and imagery evoke calls to Langston Hughes’s I Too. It’s a Super Bowl Halftime straight out of Spike Lee’s 2000’s flick, Bamboozled.

“I too, sing America. I, too, am America.”

Kendrick follows in the shadows of many Black Americans in film, music, literature, and even sports who have attempted to illustrate their love for being a Black American while acknowledging the uncomfortableness of Blackness not being digestible for America. It isn’t a unique concept. And once my high from the visually elevated performance ceased, I felt conflicted. Right before performing “Not Like Us,” after teasing us earlier following “Peekaboo,” Kendrick says “40 acres and a mule, this is bigger than music.” But for who?

Recalling certain terms and imagery such as “The revolution won’t be televised” and using Black bodies as symbolism at the biggest, profitable American sporting event — being a Black American can be such a conflicting identity. Kendrick’s theatrical retelling of culture, race, and integrity in the pursuit of the American Dream we’ve been sold (and bought), offered some catharsis. Poached upon one of the lamp post set props are a group of Black men wearing extra large white tees, baggy denim jeans, gold grills, and caps. It’s the Oakland dance group Turf Feinz. A recorded audio of beatboxing and talking plays faintly underneath as Kendrick raps the ending of the third verse to what has become Kendrick’s crowning glory song — “man at the garden.”

Since the release of GNX, “man at the garden” has emerged as one of the album’s standout tracks. While songs like “tv off,” “luther,” and “squabble up” have gone viral and instantly dominated the Billboard charts, tracks like “man at the garden” and “reincarnation” have become the subject of fan attachment and deep analysis. But there’s a subtle pain that “man at the garden” seems to remedy not just for his fans, but for himself. In Apple Music promotional videos with Timothee Chalamet (which was a choice), Kendrick without prompt constantly acknowledges the song. Emphasizing the importance of why he made it and most importantly, how it signifies the place Kendrick has finally arrived at. The moment when he doesn’t deny himself, but enforces his place. As a rapper and as a Black man.

The state of who he is, or at least how we perceive him to be, has been on full display for observation and critique. The dialogue between Kendrick Lamar and the Great Beef of the Blog Era Superstars has become a springboard for conversations around race, anger, the commercialization of “the culture,” and the ever-evolving question of what it truly means to “protect” it. His interview with SZA for W Magazine gave his first verbal explanation of “Not Like Us,” yet somehow, it left me even more confused about his stance and why this particular moment was necessary.

When asked in the interview what “Not Like Us” means, he responded:

“Not Like Us is the energy of who I am. The type of man I represent… this man has morals, he has values, he believes in something, he stands on something. He’s not pandering.”

The response only deepened the public’s confusion (and my own) about the why of this once-in-a-lifetime rap beef. And with the world at his feet, I figured after the Super Bowl we would move past “Not Like Us.” I’m more interested in what comes next. How he plans to move forward once it all dies down (if it ever does). Kendrick’s performance tackles criticisms of himself or of Black America being “too loud, too reckless, too ghetto.”

But there’s a certain irony to “man at the garden.” Sonically, it pulls from Nas’ classic “One Mic,” a song released in December 2001 in the aftermath of the Great Beef of Brooklyn (Jay-Z) vs. Queens (Nas). After Summer Jam screens and baby mama innuendos, Nas partnered with Chucky Thompson to create a track that reflected on the storm rather than fueling it. In an interview with HipHopDX, Chucky recalled:

“‘One Mic’ was a situation that was during a time that [Nas] was in the beef with Jay-Z. I knew that that beef wasn’t gonna last forever. My whole thing was, ‘Okay, so what do we do after this whole beef is over? How do we come out of this?’”

And that’s the question I have for Kendrick. We get it. They are not like us. But what now?

Both artists use music as an altar for confronting anger and existential questions. Nas’ rising crescendo of hope versus Kendrick’s whispers erupts into roars of cultural resentment as shown through the skits performed last night. Through the lyrics of their respective songs, both men engage in an unfiltered conversation with God. It’s a reckoning with the world and their place in it.

Leading us to question: What does it mean to channel fury into creation? And how is that supposed to look?

We know Kendrick to be hyper-aware of his community, his Blackness, his identity, and how all of it shapes him. And he’s always wrestled with that in his music. Whether that’s through his hometown (GKMC), his identity (TPAB), his place in American society (DAMN), and finally with himself (Mr. Morale). “man at the garden” encapsulates all of that energy while carrying the same weight that “One Mic” did. So for a lot of Black men, at what point did they first recognize their anger or frustration with the world around them? And more importantly — what did they do with it?

During his press conference, Kendrick answered this. Kind of.

“I know the most meanest and most aggressive individuals, but they can’t express themselves the way they want to, so they resort to other things. But I have the tools necessary to communicate it effectively. I gotta make records for them. I gotta make ‘Man at the Garden’ for them. I gotta make ‘Reincarnated’ for them because they feel that way, but they can’t project it.”

“I think a lot of Black men, including myself, feel like we have to produce through our pain instead of healing our pain. And I think sometimes that realization doesn’t come until later—when we’re in our thirties, when we have families, when we’re deep in relationships, and things start to surface. We realize that we have this deep-seated pain, but also anger,” says Dr. James Norris, also known as Dr. J. An assistant professor at the University of the Cumberlands in the Clinical Counseling and Counselor Education Program, he’s also a licensed practitioner in Washington State, Arizona, and California.

“Because that pain is connected to a reality we haven’t fully processed. We’re always on guard when we step outside our homes. We lose people. We don’t have a space to share that deep pain. And when there’s nowhere for it to go, that pain turns into anger because we’re tired. Tired of producing through the pain. Tired of not having a place to release it without coming under attack. And I think that is the beauty of hip-hop.”

Kendrick has called himself the Boogeyman. I’m not sure how much of the Candyman legend is true, what’s fake, what’s exaggerated. But the story tied to the character is rooted in anger. Being so angry about your lived experience that you haunt every single generation that says your name. And I wonder about reincarnation: how sometimes, our anger is not just our own, but that of our ancestors.

“Absolutely,” says Dr. Norris. “I believe it. I have to believe that if I believe in generational trauma. If I say generational trauma exists, then there’s generational anger and historical anger that comes through the DNA and this process of us becoming. We have to do something with it so we don’t keep passing it on.”

Because most of the time, we’re just passing the anger, the trauma, and our disappointments onto the next generation, and then they have their own. And then that compounds it. Even Kendrick’s evolution has been about trying to work through the trauma that was put on him, the anger that was placed on him, and then his own. When I was listening to both songs, I felt like they might have been coming from two different perspectives on where they were at in their lives. Nas released this on Stillmatic, and Stillmatic came after the Jay and Nas beef. But when I was listening to “One Mic,” it felt more introspective, whereas “man at the garden,” especially at that moment, felt more existential. It felt personal.

And as the saying goes, “The child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth”: “I’ll burn this b***h down / Don’t play with me or stay with me / No one’s safe with me.”

I did it with integrity, but niggas still hate on me. Just wait and see / More blood is spilling, it’s just paint to me

Kendrick Lamar, “man at the garden”

“I did it with integrity, but n****s still hate on me. Just wait and see / More blood is spilling, it’s just paint to me. I would like to know more about that bar,” Dr. Norris wonders. “What are you speaking to directly? What happened that triggered this? Why is it so important to communicate to Drake and others that they’re not like us? What is the consequence of not being that? Because there’s a lot of brothers out here that’s not that. And what would you say to those individuals who are not there yet?”

Praise for his victory run and last night aside, Kendrick is hypocritical. The revolution won’t be televised but it’s being sold through Americana imagery and marketing. And he’s not the only one. Even though he admits that he’s a hypocrite, he still contradicts himself. He might preach about protecting Black women, inviting Serena to C-Walk on Drake’s cultural grave then in the same breath, share a stage with Dr. Dre. So where’s the line here?

Dr. Norris challenges my stance. “I think that can be unfair too because I know we have to be thoughtful of who we align ourselves with. But we also have to be nuanced enough to know that Kendrick is not responsible for anything Dr. Dre has done. We also have to understand the rich history of Kendrick becoming who he is and who he’s connected to. So maybe aligning with Dre is out of respect and paying homage, not necessarily a sign that he agrees with everything Dre does. As a community and as viewers, we have to be nuanced in our thinking. Because he’s telling you, ‘I stand on principles.’”

Principles. Our principles as people inform the decisions we make. The more intentional we are, the more genuine our decisions and values feel. Since this beef started, I’ve been thinking a lot about Kendrick’s legacy. He’s done a great job with — for a lack of a better word — propaganda for “Not Like Us” to mean more than him dissing Drake but refuses to give us anything more outside of “I live and die for hip-hop.”

“Where is the landing place after the crash out?” Dr. Norris questions. “Because all of us, at some point, will have a crash out, a fall, a fall down. But who’s there to catch us? I think, as a community, as the culture, do we have enough grace to also catch Kendrick? He’s going to need a landing place because he’s releasing so much, right? But as consumers of the music and believers in the culture, can we have grace?”

Born in Inglewood, later moving to the east side and eventually to the San Fernando Valley (just 20 minutes from the city), Dr. Norris saw through the guise of The Pop Out as something deeper, something unspoken.

“When The Pop Out happened, I thought of Nipsey. I think this anger, this pain, this frustration isn’t just about Drake. Kendrick even said it at The Pop Out: ‘Shit ain’t been the same since we lost Nip.’ So there is still some deep pain within the city.”

So do we underestimate grief?

“Most people don’t grieve,” says James. “They just get through.”

James reflects on his journey and the loss he’s experienced due to gang violence. “My mom was very intentional about moving us out of the city because she knew if we had stayed, she already knew what it was going to be. Nip, Kendrick, and others would have been me on some level,” he explains. “Even though I saw the same things, even moving away but not at the same scale. That’s why I appreciate Kendrick so much because he’s finding a way to process the real pain that many Black men are experiencing in LA and beyond. In a raw, authentic way that many Black men don’t get the opportunity to do unless we’re creating intentional spaces.”

So we have to crash out for the sake of what we need to continue? James says no. Because not everyone makes it after the crash out. “I think it’s really important to have the tools to navigate yourself through the crash out,” he says. “Your very highs, your very lows, and the ones you never came back from will be a part of your legacy. You renew yourself with a new purpose and a new understanding of yourself after you go through this run. Now, you create a legacy of transformation.”

I spent the last couple of months hell-bent on analyzing Kendrick. Him being angry (rightfully), him “getting his lick back” and how he’s no different from other Black artists who use their cultural currency for reflection on “the revolution.” But as James reiterates, “Anger happens, but it’s very nuanced. People just think, ‘They’re angry at this.’ But when we look at it from a wide lens, I think it’s great to talk about anger. Rarely do people talk about the nuance of Black men’s anger. It’s society, it’s the marginalization, it’s the pain we’ve seen or the pain of you not allowing me to just be. Now, we can communicate to the people we love what we’re dealing with. They can better support us, be there for us, or just walk with us while we’re trying to navigate it.”

“man at the garden” is a moment of meditation. A moment of frustration and contemplation. Before the Super Bowl Halftime, I thought I had the ideology of Kendrick Lamar’s brand of Blackness figured out. But, I’m still conflicted. Kendrick might be too. Being a Black American is a contradicting game. I just hope Kendrick doesn’t misuse his influence.

For More Information of Dr. James Norris:

IG: @ithemba.us

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/drjphd