Former Auditor General Anand Goolsarran says that instead of the government unleashing criticism of its four years of consecutive negative reviews on Transparency International’s (TI) Corruption Perception Index (CPI), it should look at ways to improve its ranking.

He believes that denouncing the findings emboldens those who are corrupt as they may feel that unlawful acts fall on deaf ears.

“An improvement in a country’s CPI score as well as its ranking is considered an indicator of a reduction in the level of corruption. The first step in the fight against corruption therefore must be the acknowledgement of the existence of corruption and the extent to which it is perceived to exist,” Goolsarran stated in his “Accountability” column published today.

“The failure to do so will only serve to embolden those who are bent on indulging in corrupt behaviour that enriches the few at the expense of the vast majority of the citizens,” he added.

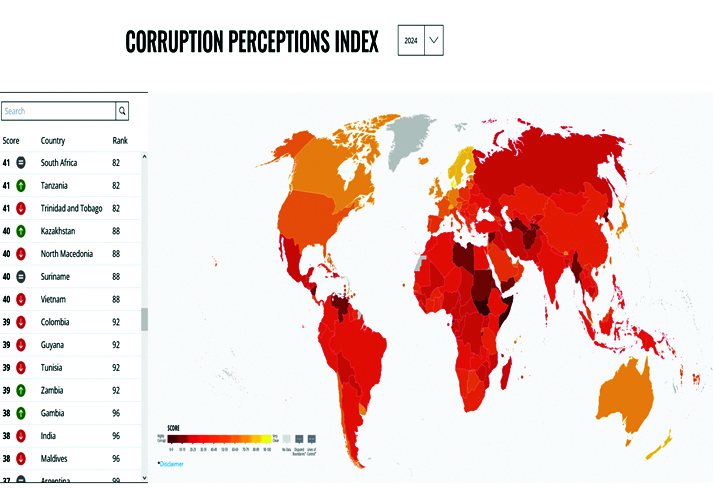

TI’s 2024 CPI gave Guyana a 39 out of 100 ranking, which President Irfaan Ali has dismissed as riddled with “political biases” rather than grounded in fact. Ali also pointed out what he described as inconsistencies in past rankings, arguing that the previous government received higher scores despite significant governance failures. The president further alleged that the individuals heading TI’s local chapter have personal biases against the government, with some even filing lawsuits against it.

Highlighting that for the English-speaking Caribbean, Guyana has been jostling in the bottom places with Trinidad and Tobago for four consecutive years, Goolsarran said that it could be assessed from past reports that improvements in the rankings came when anti-corruption measures were taken, and it was during the David Granger administration.

“In 2012, Guyana’s CPI score was 28 out of 100. Eight years later, it moved to 41. This 13-point increase occurred mainly during the period 2016-2020 when its score increased from 29 to 41. The largest increase was in 2016 when Guyana scored a five-point increase, moving from 29 to 34,” he said.

“This enhanced performance was mainly due to several anti-corruption initiatives undertaken. These include: (a) holding of local government elections in 2016 and 2018 after a hiatus of 22 years; [and] (b) several amendments of the Anti-Money Laundering and the Countering of Financing of Terrorism Act 2009 to comply with the requirements of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). The previous government had declined to amend the legislation based on recommendations made by the FATF, despite the threat of sanctions, including blacklisting.

“(c) Conduct of numerous forensic audits of state institutions and the involvement of the Special Organised Crime Unit in instituting charges against those who have been fingered in the abuse and misuse of state resources. (d) Establishment of the now disbanded State Assets Recovery Agency in keeping with a key provision of the UNCAC relating to freezing, seizure and confiscation of property. (e) Activation of the Public Procurement Commission for the first time since its establishment by constitutional amendment of 2001 to provide the much-needed oversight of Guyana’s procurement processes.”

Noted steps taken were also the activation of the Bid Protest Committee to investigate complaints from aggrieved suppliers and contractors in relation to the award of public contracts and the appointment of new members of the Integrity Commission which remained dormant following the resignation of the Chairperson in 2006.

Goolsarran also listed the, “Revision of the Code of Con-duct contained in the Integrity Commission Act as it relates to ministers, parliamentarians and other senior public officials. (i) Establishment of Guyana’s Extractive Industries Trans-parency Initiative. (j) Tabling of draft legislation for the establishment of the Petroleum Commis-sion. (k) Enactment of the now repealed Natural Resource Act 2019. (l) Enactment of whistleblower protection legislation. (m) Amendment of the Fiscal Management and Accountability Act to provide for the financial independence of constitutional agencies.”

He noted that in its analysis of the Americas, TI cited Guyana as where “state capture by economic and political elites fosters misappropriation of resources, illicit enrichment and environmental crime”. Referencing state-capture.org’s meaning of state capture, he said that the body said it was “the seizure of political, legal, and economic levers of a nation by an unaccountable elite.

“It takes place wherever public institutions, government officials, and the justice system fail to safeguard a nation’s democracy, rule of law, and resources. When state capture takes hold, the machinery of the state starts to favour specific groups rather than the public interest. State capture does not exist in national vacuums – it is typically enabled by transnational networks, and its proceeds are routinely laundered through the global financial system. Wherever it occurs, state capture leads to endemic corruption, poverty and socio-economic disparity, human rights abuses, media censorship, resource depletion, and environmental degradation.”

Goolsarran was also quick to point out that left unchecked, state capture can escalate into armed conflict, atrocities, and mass migration.

Noted too was TI’s reference to Guyana’s very low level of transparency and law enforcement, despite having in place anti-corruption institutions.

The world’s largest transparency advocacy body also had highlighted “attacks on dissenting voices, activists and journalists” as being increasingly common here.

“These are serious indictments on the government which has once again sought to discredit the CPI results, arguing that the index is based on perceptions and not actual levels of corruption,” Goolsarran posited.

For countries with non-democratic forms of government, Goolsarran said that corruption tends to flourish where, among an exhaustive list, there are weak institutional and governance frameworks; vague, archaic and cumbersome rules; high bureaucratic discretion; lack of transparency, especially as regards the award of contracts as well as entering into agreements with other parties. He also listed the lack of timely and proper accountability for the use of public resources; political interference in the decision-making of key agencies and restricted flow of information on government programmes and activities.

There are also nepotism and favouritism; appointments to key positions based on considerations other than those relating to professional and technical competence and weak political accountability.