The Diagnosis Trap

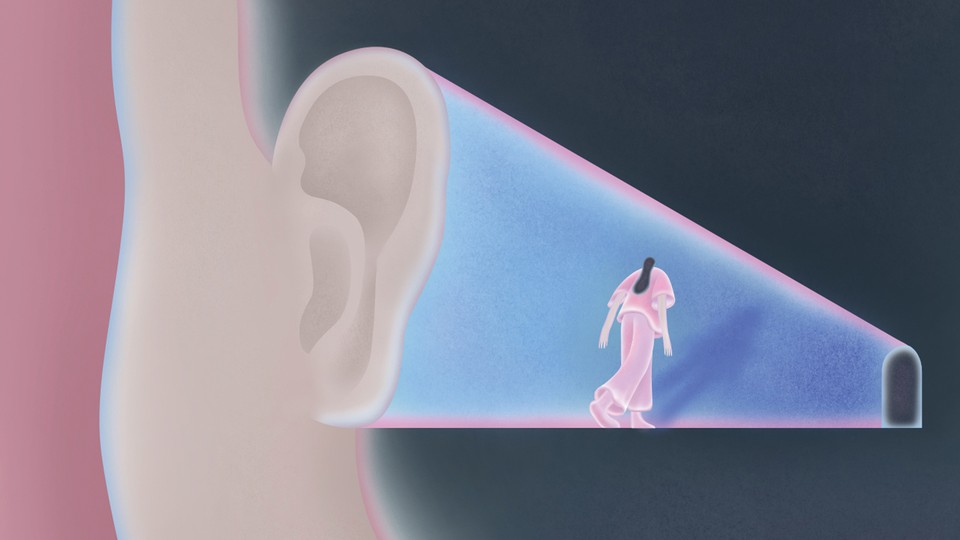

Doctors have their stories to tell about mental illness. But what about the stories we tell ourselves?

Let me explain something about me: When I was 12, I started having panic attacks, brought on by fears that I couldn’t shake, even though I knew they were irrational. I was terrified, for example, that I’d become depressed—but I’d never been depressed before, and didn’t feel depressed. My junior high school devoted a series of assemblies to warning us budding teenagers that we were entering the most dangerous years of our lives, now ripe targets for cutting, suicide, eating disorders, overdoses, AIDS, and fatal car accidents. I would spend hours, even days, worrying that one of these things might be coming for me. My mind seemed to spin out of control—I couldn’t stop fixating, I couldn’t calm down, and I couldn’t understand what was happening.

Finding language to describe suffering of any kind is hard, but eventually, fearing I was going irreversibly insane, I tried—first for my mother, then for a doctor. Soon I was told there was a name for my particular distress: obsessive-compulsive disorder. Receiving this news at 13 was both relieving and shattering. (And surprising. There had been no assembly suggesting we watch out for anxiety disorders.) With the diagnosis came explanations and context for what I had not been able to interpret, as well as a body of scientific knowledge about treatment. Still, OCD can be an upsetting diagnosis, partly because according to current psychiatric understanding, it’s a chronic illness. You don’t typically get cured. You “learn to manage it” and, like most chronic conditions, it ebbs and flows based on a variety of factors. I felt horror at being indelibly marked and feared that I’d never get back to “my old self.” Who was I now?

Rachel Aviv begins her nonfiction debut, Strangers to Ourselves: Unsettled Minds and the Stories That Make Us, with the story of her own childhood introduction to psychiatry—briefer and more unusual than mine. At 6, she tells us, she abruptly stopped eating. She refused to say the names of food, “because pronouncing the words felt like the equivalent of eating,” and refused to say the number eight, because it sounded like ate. That year, she was admitted to the eating-disorders unit at Children’s Hospital of Michigan, thought to be the youngest person on record to be diagnosed with anorexia. Her doctors were perplexed, speculating that her anorexia might be related to the stress of her parents’ divorce. Aviv didn’t understand her diagnosis, its implications, or its cultural associations—she couldn’t even spell it. “I had a diseas called anexexia,” she wrote in her diary two years later.

In the ward, she was guided by older girls, from whom she learned the conventions of the disorder. “I hadn’t known that exercise had anything to do with body weight, but I began doing jumping jacks with Carrie and Hava at night.” She refused to sit down after the girls taught her the phrase couch potato. But eventually Aviv ate because she’d been forbidden to see or speak to her parents unless she did. “My goals realigned.” She was discharged from the hospital after six weeks, and assimilated back into her old life, eventually consenting to sit down with the rest of her class at school. The illness lifted as mysteriously as it had descended. From here, she suggests, she went back to a normal, healthy life.

“To use the terms of the historian Joan Jacobs Brumberg, who has written eloquently about the genesis of eating disorders, I was ‘recruited’ for anorexia, but the illness never became a ‘career,’ ” Aviv writes. “It didn’t provide the language with which I came to understand myself.” She proposes that she recovered because she was too young at the time of her illness to decipher or internalize the cultural and psychiatric narratives that attend it. She had no “insight,” a term used by psychiatrists to describe the quality of being self-aware and rational regarding one’s illness. Typically, insight is crucial to a good prognosis: If you have insight, you have what doctors would call the “correct attitude to a morbid change in oneself,” as a 1934 paper in The British Journal of Medical Psychology put it. But Aviv, pointing out that a correct attitude to a morbid change “depends on culture, race, ethnicity, and faith,” supplies a different, more acerbic definition of insight: “the degree to which a patient agrees with his or her doctor’s interpretation.”

Being an “insightful” patient in the traditional sense demands accepting the diagnostic categories and language on offer, she writes. (Failure to correctly perform insight can also play a role in the decision to institutionalize a person without their consent.) And insight, Aviv argues, has its dangers. Adopting a dictated narrative about your mind can change your outcomes, for better and worse. “I wasn’t bound to any particular story about the role of illness in my life,” she writes with relief. “There are stories that save us, and stories that trap us, and in the midst of an illness it can be very hard to know which is which.”

As a writer who has reported on medicine, education, and criminal justice for The New Yorker since 2011, Aviv reanimates this early chapter of her life to introduce the collection of essays that follow: five profiles of people whose stories defy or complicate psychiatric models of understanding the mind. Aviv is skeptical of psychiatric diagnosis and the language that accompanies it not because she’s fundamentally anti-psychiatry but because psychiatry is a limited and constantly shifting discipline, deeply influenced by the foibles and fashions of culture. More broadly, her interest is in the parts of existence that William James called the “unclassified residuum,” which frustrates scientists whose desire, he wrote, is “a closed and completed system of truth.”

Each of the people Aviv profiles offers evidence of a different shortcoming of Western psychiatry. Ray is a ruminative depressive who was institutionalized in 1979. Because his illness coincided with a sea change within modern psychiatry, he was offered two very different explanations—and treatments—for what ailed him. One approach endorsed introspective therapy to promote “understanding” of the fundamental personal and social maladjustments producing his distress; the other, corresponding with the rise of the “chemical imbalance” theory of mental illness, proposed that his depression was a natural, biochemical phenomenon, and required psychopharmacology. Ray had begun, medically speaking, as a man with burdensome personal flaws, and emerged a man with bad neurochemistry. “Who is Ray Osheroff, now?” he wrote, late in life, still miserable.

Then there is Bapu, a young Indian woman who in the 1960s experienced a spiritual awakening and became convinced that she had been chosen to “immerse myself in the ocean of devotion,” as she wrote in her journal. She spent hours a day in her prayer room, began dressing and living like a Hindu ascetic, and repeatedly tried to leave her husband and children to live in a monastery. She believed she was a bride of Krishna’s. Bapu’s husband took her to a Catholic psychiatrist trained in Western approaches, who pronounced her schizophrenic. She insisted that she was simply joining a millennia-old tradition of Hindu mystics.

Bapu refers to herself as a madwoman or a lunatic more than a dozen times in her journals, but only sometimes with despair. She saw her alienation from society as proof of her insight. Her inner world had come to feel more substantial than the reality to which her family was bound. The saints she admired had also ruptured ties with family and devoted their lives to phenomena that others could neither see nor touch. Ramakrishna, a nineteenth-century mystic, told his devotees that madness was a mark of devotion and should never be mocked.

Bapu lived for many years on the streets, suffering both physically and psychically, but “she drew from a rich tradition that gave her anguish purpose and structure.” Aviv asks: Whose version of Bapu’s story should be the authoritative one?

The bleakest of the case studies is Naomi, a young Black American who grew up in the 1980s and ’90s in a Chicago housing project that a Housing Authority official described at the time as a “hell hole.” The grinding poverty and violence of her childhood gave way to the grinding poverty of her adulthood: As a teenager, she lived in a shelter with her newborn, but became a teacher’s assistant and went to community college at night. She loved to read and to write music, and after joining a writing group began searching for Black-women-centered histories of American racism, poverty, and police brutality. “She felt debilitated by the historical resonances of her own story,” Aviv writes. “She suddenly had language to describe the kind of pain that had haunted her family for generations.”

Naomi’s grief was all-consuming. She became depressed, and then—after a traumatic childbirth experience—psychotic; a year later, she leaped off a bridge after dropping her twin sons into the water below, believing she was saving them from a life of thwarted potential and unjust suffering. Her subsequent journey through the legal and medical systems, which failed her spectacularly, was complicated by the fact that her delusions were rooted in something so absolutely real and grimly central to her experience. “She wants to convert people into not being racist and accepting her people,” a doctor noted in Naomi’s chart during one emergency-room visit. In some contexts, Naomi’s complaints were described as “bizarre,” evidence of her incapacity—in others, as “astute observations about the society in which she lived.” Which responses to racism are pathological, and according to whom, and when?

One of the pleasures of this book is its resistance to a clear and comforting verdict, its desire to dwell in unknowing. At every step, Aviv is nuanced and perceptive, probing cultural differences and alert to ambiguity, always filling in the fine-grain details. Extracting a remarkable amount of information from archival material as well as living interview subjects, she brings all of these people to life, even the two whom she never met. I zipped through each essay—propelled by curiosity—yet needed to take breaks between them, both to recover from the intensity of the human experience described and to sit with the implications of the argument Aviv is building, which suggests that it may be more harmful than helpful to see yourself the way doctors see you.

As I read, I found myself with a lingering unease about Aviv’s own relationship to her broader subject, sensing more complication there than she initially allows. She presents herself at the outset as someone who was spared a lifelong struggle with mental illness because she was just too young to become ensnarled in what the philosopher Ian Hacking calls the “looping effect,” when a diagnosis becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. A new diagnosis can change “the space of possibilities for personhood,” he writes. Unlike the girls Aviv met when she was 6, some of whom never recovered, she is able to study this process rather than live it.

Did Aviv escape an external narrative quite as cleanly as she wants to believe? We are left to wonder until her final essay, in which she wrestles with this question directly. “Laura” tells the story of a young woman who was put on a string of medications in adolescence, none of which seemed to significantly ease her misery, a failure that led to additional medications in various combinations. Here, more explicitly than in her portrait of Ray, Aviv joins an existing discourse about psychopharmacology, raising by now familiar concerns about the overmedication of Americans, and the impulse to treat regular human unhappiness as pathological. And here, she introduces her own fraught relationship with Lexapro.

Aviv started medication in her late 20s, as her writing career was getting under way, to assuage social anxiety and ambient feelings of inadequacy. Her first six months on Lexapro was, she thought, the best period of her life. Her social anxiety vanished. She also felt somehow intrinsically different—more playful, more loving, more engaged in the world. This recalled a telling moment from her childhood diary: “I had some thing that was a siknis its cald anexorea. I had anexorea because I want to be someone better than me.” This central issue—wanting “to be someone better than me”—seemed neither produced by her pediatric brush with diagnosis nor helped by it. She may have escaped a “career” of illness, but this feeling stayed, until Lexapro.

Soon Aviv became disconcerted that so many of her female friends were also taking Lexapro and loving it. “These more and more seem like Make The Ambitious Ladies More Tolerable Pills,” a friend wrote, echoing her suspicion that the medication was more fad than necessity. But Aviv’s attempts to quit didn’t go well—stopping the medication brought on terrible depression (which can be a passing withdrawal effect of some antidepressants), and she always started her dose again. A couple of years later, still on Lexapro, she decided she wanted to be a mother. Two weeks after going off the medication upon learning she was pregnant (as is sometimes advised), she was immobilized and quietly imagining a miscarriage. Her doctor grew alarmed and suggested she resume the medication. She did, and three weeks later, she writes, “I felt connected again to my reasons for having a baby.”

Aviv tries to take stock: What to make of the enormous hold Lexapro now seemed to have on her life, despite her belief that she’d avoided an illness “career”? She describes growing confused about her “baseline self.” What if she is not the achieving, albeit anxious, person she’d been before Lexapro, the identity she’d embraced as “true,” but “the more dysfunctional self that had occasionally resurfaced—most visibly when I was six and hospitalized”? Aviv is negotiating a complicated formulation here. First, she assumes a “baseline self,” a concept that makes intuitive sense but also stands in tension with the evidence she’s offered throughout her essays that the “self” can be determined or altered by external factors. Then she makes a distinction between her “baseline self,” which is functional, and the “more dysfunctional self” that sometimes surfaces. Where did this narrative come from? What is the self? Who gets to say? “To continue as the person I’d become I needed a drug,” she writes after more than a decade on Lexapro. “I wanted my children to remember the version of me that took Lexapro.” “On 7.5 milligrams I’m a better family member,” she tells Laura about her decision not to lower her dose. Who is Rachel now?

The existence of this book—and Aviv’s career as a journalist who frequently investigates the depths of human suffering, whether among refugee children who sink into coma-like trances or senior citizens taken from their homes and denied autonomy—indicates unfinished business of the generative sort. She’s drawn to the disorienting terrain of shifting self-knowledge, alert to the trauma of having one’s agency stripped by an outside authority or an imposed narrative. Still, she doesn’t argue for pure self-determination. As I read, I kept returning to Aviv’s early diary entry, “Here let me explain something about me. I had a diseas called anexexia.” A second moment from the same era also stuck with me. She writes that when she first arrived on the ward, she asked one of the older girls there over and over, “Do you think I’m weird?”

This feels like the core human impulse that Aviv is attempting to parse. Every person in Strangers to Ourselves writes to understand their mind. Ray spends decades on an autobiography; Bapu has a kind of graphomania, sometimes scrawling diaries on the walls; Naomi writes songs, a novel, and a memoir; Laura has a blog; Aviv gets access to the many journals kept by Hava, one of the girls she met in the hospital. When we become strangers to ourselves, we are compelled to narrativize. And then we need to know what others make of that story, how they understand us, so that we can understand ourselves. The question “Who am I now?,” while directed at the self, cannot be answered only by the self. It requires traversing between the meaning we make inside ourselves and the meaning we encounter in community. Aviv’s subjects, she writes,

described their psychological experiences with deep self-awareness, but they also needed others to confirm whether what they were feeling was real. It didn’t matter whether they believed they were married to God or saving the world from racism—they still looked to authorities (mystics for Bapu, doctors for others) to tell them how and why they were feeling this way. Their distress took a form that was created in dialogue with others, a process that altered the path of their suffering and their identities too.

Approved insight, the kind that informs “correct” narratives, exerts real and lasting power, whether damaging (Aviv’s focus) or healing, as is often the case. But Aviv is more preoccupied with insight in the philosophical sense—finding order and meaning in one’s own story—which is anything but straightforward or static. I am not the person I feared I would become after my diagnosis at 13, and the diagnostic language and medication I was offered at that time allowed me, paradoxically, to feel less defined by my experience of anxiety. Still, I have an ongoing, sometimes uneasy relationship with diagnostic categories and with medication—a relationship that necessarily changes as I change. Aviv reminds us that Who am I now? is less a momentary question than a koan that suffuses every life, an invitation to revisit and revise the conundrum, whoever you are and whether or not you have a diagnosis. All of Aviv’s subjects, herself included, live at the mercy of social and medical constructions, and yet strive to shape and reshape their irreducible, protean selves. It is the most human drama. It doesn’t seem weird at all.

This article appears in the October 2022 print edition with the headline “The Diagnosis Trap.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.