Scottish writer Alex Renton tells bloody story of family's role in Caribbean slavery

Over the past few years it’s been increasingly revealed – or rather, re-revealed – just how much of Britain’s wealth – which built and ran factories, canals and industrial machinery, the stately homes, the museums, the universities – came from “the West Indians” – the UK-based absentee landlords who profited from the transatlantic trade in African people. August institutions were created, sustained and enriched by the unpaid labour of enslaved Africans who produced cocoa and cotton, indigo, coffee and, cruellest of all, sugar, on estates throughout the Caribbean.

The British would have been aware of a lot of this a long time ago, of course, if they’d just read Eric Williams. It was he who wrote in the 1940s in Capitalism and Slavery that the bricks of Liverpool, England’s biggest slaving port, were cemented with African blood – an unforgettably sickening but almost literal metaphor.

Recently, the Scots writer Alex Renton discovered his own family’s once quite substantial fortunes (one branch, the Fergussons, had a grand house in Ayrshire with a dozen servants) also came from slavery. The house held boxes of old diaries, letters, photo albums – but although his grandfather was their informal archivist, their Caribbean-related contents were not discussed.

Eventually Renton read them for himself, deciphering the cramped cursive script from the late eighteenth century onwards, as well as documents that had “all the clarity of a punch to the stomach.” When he first saw an inventory of family property in Tobago, which included the names (they had no surnames) and “value” of 70 enslaved people, “I felt nauseous…my ancestors were indeed plantation owners in the British slave colonies, farmers of human beings.”

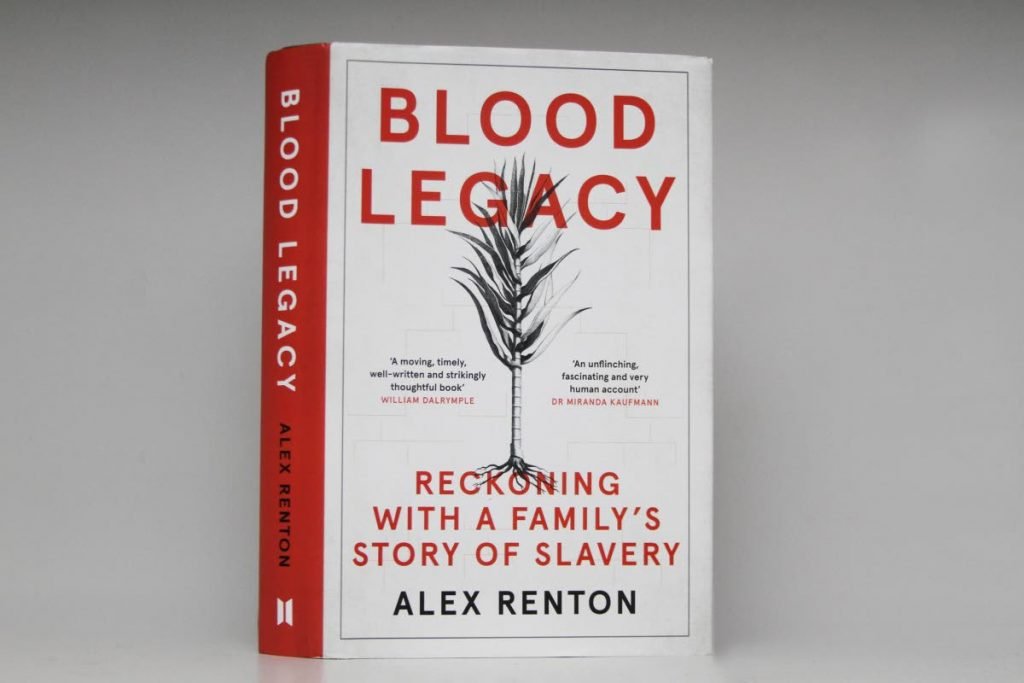

Unlike those ancestors, though, obviously, Renton, a campaigning journalist, didn’t put the archives back in the basement. Instead, jolted out of ignorance and into action, he wrote a book based on them: Blood Legacy: Reckoning with a Family’s Story of Slavery.

Renton’s family’s involvement shouldn’t have come as a surprise (though, as in this part of the world, little is taught in the UK of the history of slavery): the Scots played a disproportionate part in the extortion of profit from this region, whether as overseers or owners or industrialists like James Watt, who made money from his new, improved steam engines being used to work sugar mills.

Firmly based in the family records, this is not just a history but also a memoir of sorts, often horrified and, inevitably, often horrifying.

Renton visited the sites of the former family estates, at Bloody Bay in Tobago and Rozelle, in St Thomas-in-the East in Jamaica, recording with a mixture of naivete and journalistic inquisitiveness his discussions with local people on slavery, race, reparations and their attitudes now to white people.

The book of course reveals too the thoughts and feelings of a modern, liberal white Briton about a scandalous past, the depths of whose monstrosity, and whose personal implications, he had never suspected.

Many of the family papers Renton found were minutely detailed accounts sent to relatives in Scotland by those who had gone out to the Caribbean to run the estates, or the managers they hired. When one comes across hitherto unknown documents, it’s tempting to quote them exhaustively. So much of the book is occupied by the records of the rising and falling fortunes of the estates.

The section on Tobago contains valuable new information that ought to be accessible to local scholars, and Renton discussed with Dr Susan Craig-James, author of a two-volume history of Tobago, ways of ensuring this happens.

The young James Fergusson, sent out to Tobago, acquired the estate there in 1774, and reported back to his older brother Sir Adam on the cost of the land, the labourers bought to clear and work on it, and the illnesses, incurable in those times, that afflicted them at frightening rates. (On the Jamaican estate, in one ten year-period, more than half the older children and adults who were bought to work there had died.)

James is said to have had a compassionate attitude to Africans at first, yet ended up designing a silver brand to burn his and his brothers’ intertwined initials onto the skin of the estate’s labourers. It’s tempting to think it was the vengeance of Moko that, by the time the estate started to yield cotton crops, after four years on the island, James was dead, at 31, of a long, unspecified disease.

The Jamaican section of the book covers the Fergussons’ longer involvement there, from 1769, and indeed much of the history of that country and the Caribbean up to and after Emancipation: the rebellions that finally led to the end of slavery, the abolition movement in the UK, and Britain’s outrageous “compensation” – to the enslavers – of £20 million. It addresses the topic of reparations, and the fact that Emancipation was in many respects a legal technicality, which certainly did not lead to equality or the end of poverty or racism in the Caribbean.

There are glimpses of the lives of the people on whom the estates’ profit and loss depended. Some of these stories deserve a longer telling, although they make harrowing reading as it is; and although one local interviewee told Renton more “slavery porn,” about deaths on plantations and slave ships, wasn’t needed. (She wanted to know how “the white people (are) going to work out what they are going to do and be for the future.”)

Still, you can’t help but be gripped by the fragmentary story of Annie, a “house slave” and the mother of five (surviving) children by one of Rozelle’s managers, Archibald Cameron; after he was fired and returned to Scotland, Cameron made an offer to buy his family, but never followed up on it, thus abandoning Annie and their children to wretched fates.

There is so much human suffering in those few lines.

Then there’s the amazing Augustus Thomson, who turned up on Sir Adam Fergusson’s doorstep in London in 1781: he had run away 18 months before from Rozelle, where he was listed as a “black doctor,” to seek redress for cruel treatment by the estate manager. Skilled and intelligent but illiterate, he had dictated a letter, included in the book, describing how among other things he had been ordered off the estate, he and his family whipped and otherwise tortured, his house set on fire and his belongings stolen.

Astonishingly, he was not unwilling to return; Sir Adam promised at first he would not be punished if he did his “duty”– but later changed his mind. Thomson, his unlikely belief in justice crushed, absconded again; what became of him is uncertain, but Renton has unearthed two grim possibilities.

As he and other writers uncover the unpleasant truths about Britain’s slaving history, some Britons aren’t taking it well, denouncing it as “rewriting” the nation’s imaginary glorious imperial past. It’s a big step from believing one’s country was a benevolent power, enlightening various benighted natives, to acknowledging that much of its prosperity and many of its treasures are actually bloodstained loot plundered from imperial subjects who for centuries were treated worse than animals.

Some individuals and institutions, such as Glasgow University, have faced up to the fact that they owe their existence or endowments to the tortured lives and premature deaths of enslaved people, and are trying to make some amends.

Renton says in his introductory notes that he and some of his relatives are donating to “educational and youth welfare projects” in the Caribbean and the UK; he is giving the profits from this book to such causes, though he simultaneously concludes, “the damage done by slavery cannot be repaired, nor the descendants of the people who were enslaved adequately compensated.” He believes, however, that the consequences can be changed.

Blood Legacy, then, is far more than a personal history of one family’s shameful involvement in the darkest chapter of Caribbean and British history: so much more, in fact, that it sometimes threatens to overwhelm. Were many of these facts as well known as they should be, one could argue that this could have been a more concise memoir, rather than a compendium on Caribbean slavery and its aftermath. But for many people, on both sides of the Atlantic, it will be an enlightening and readable, if deeply painful introduction to the entire topic.

Alex Renton has worked for national and international newspapers as a war correspondent, food writer and investigative journalist. He lives in Edinburgh with his family. Blood Legacy: Reckoning with a Family’s Story of Slavery is published by Canongate.

You can also visit the website at https://www.bloodlegacybook.com/

Comments

"Scottish writer Alex Renton tells bloody story of family’s role in Caribbean slavery"