(ThyBlackMan.com) What does it take to make a change in our society? That may depend on the type of change. In this case, I’m speaking of the difference in how people view each other, especially racial groups. Mainly, Caucasians and people of color. This change would require respect for different cultures. So, how do we get there?

It will require acknowledgment of the fact that a problem exists. People try to avoid this simple fact. They want the origin of our racial discontent to disappear. Still, it cannot and will not until the issue acquires resolution, and this takes a willingness to accept and understand the circumstances of how the United States arrived in this negative position. In other words, the ugly truth, a truth that entails Africans kidnapped from their homeland and sold to varied countries along the route to the U.S. Taken away from our stolen legacy. Like Egypt, which is on the continent of Africa, was annexed to the middle east-stolen. A stolen people that you can’t keep against their will under servitude for 400 years and then expect them to disappear. The subject matter will keep coming up until achieved resolution.

One can’t expect people to go through hundreds of years of maltreatment without awaiting negative innate behaviors to arise in future generations. You don’t get over 400 years of heartache and pain in the blink of an eye. African people weren’t ignorant. They just spoke different languages. People of color always had to be twice as smart and do twice as much to achieve status in this world.

Africa is the mother of humanity. We are people of high intelligence, ability, durability, swagger, style and grit. Melanin doesn’t make us lesser than whites. Throughout history, we’ve fought to right many wrongs. Numerous people have taken the step forward to fight against hatred and bigotry to improve the lives of their families and community. Rosa Parks took the step by deciding not to give up her seat on a  bus. Claudette Colvin refused to give up her bus seat on March 2, 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama, nine months before Rosa Parks. Rev. Dr. Anna P. Murray’s writings were the cornerstone for the Brown versus Board of Education for the 1954 Supreme Court case to end school segregation. Ruby Bridges, a six-year-old, escorted to school had no idea about being a proxy for integration in 1960. In 1955, Bayard Rustin was Dr. Martin Luther King’s right-hand man, organizer, and strategist. He was a gay man and arrested for refusing to register for the draft and protesting. Rev. James Reeb, while other clergy and church people initially rejected King’s mission and message, a white, Unitarian minister accepted it with open arms. There were many other foot soldiers for justice.

bus. Claudette Colvin refused to give up her bus seat on March 2, 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama, nine months before Rosa Parks. Rev. Dr. Anna P. Murray’s writings were the cornerstone for the Brown versus Board of Education for the 1954 Supreme Court case to end school segregation. Ruby Bridges, a six-year-old, escorted to school had no idea about being a proxy for integration in 1960. In 1955, Bayard Rustin was Dr. Martin Luther King’s right-hand man, organizer, and strategist. He was a gay man and arrested for refusing to register for the draft and protesting. Rev. James Reeb, while other clergy and church people initially rejected King’s mission and message, a white, Unitarian minister accepted it with open arms. There were many other foot soldiers for justice.

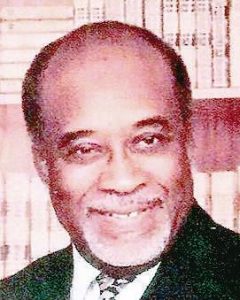

Allow me to introduce to you Rev. Dr. L.E. Bennett, The Hidden Jewel of the South. A little-known warrior, a humble civil rights activist from Texas, went from serving as a twenty-three-year-old janitor with Southwestern Bell/AT&T. Becoming the president of the Colored People’s Union, and advancing to second-line management over five districts is Rev Dr. L.E. Bennett. He fought systematic bigotry and successfully integrated the business—putting his life and the life of his family at risk in the process.

It was the 1950s and 1960s, and the war against racism and inequality in America was raging. Not much different than today. While the battle was mostly taken up by African Americans, all people eventually are challenged to take a stand—not to allow hatred and injustice to continue.

Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King encouraged Bennett, and he received certificates from the NAACP signed by Roy Wilkins, Rev. C.D. Owens, and W.C. Patton. Bennett also received media coverage, and an award from Wall of Tolerance endorsed by Rosa Parks.

Bennett pledged to do his part to fight racism and inequality after hearing JFK speak at the Alamo with Lyndon B. Johnson during their cross-country presidential campaign. Kennedy’s words rang in Bennett’s ears, “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.”

For generations, whites had limited African Americans to menial jobs, and unions had resisted workplace equality campaigns. Blacks were the most menial, demeaning, hazardous, and low-paying positions. African Americans were also taught not to expect promotions, regardless of their ability or experience. Those unfair and oppressive conditions caused deep unrest in Bennett. After being honorably discharged from the army, the 23-year-old soldier had found work as a custodian with Southwestern Bell. Over time, Bennett had monitored the company job board for possibilities regarding a more prominent position, but human resources told him that he wouldn’t be able to apply for a better job.

JFK fueled Bennett’s desire to help the civil rights movement taking place in Mississippi and Alabama spread. He combined courage, logic, eloquent speaking, relentless lobbying, and diplomacy in his quest for justice-making it possible for blacks to get prestigious jobs and promotions.

Bennett also uplifted his community by assisting in voter registration, obtaining funds to get updated plumbing to rehabilitate homes, and more. The man called the “Hidden Jewel of the South” by former councilwoman María A. Berriozábal went on to become a minister and earn his doctorate in the late 1980s. Pushed to his limit, Bennett bore the brunt of insolence, disparaging remarks, arguments, and slurs on his journey for equality. But he persisted, and now he’s a prime example of how one person can be a powerful force in ending cycles of inequality and unfairness. No one is too small to effect change. No one!

Bennett wasn’t perfect, but he didn’t need to be. None of us need to be. We need to be braver. Elie Wiesel once said, “We must take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim.”

We, as a people must have a common goal of equality. A goal to end the powerlessness that generations of systemic discrimination and racism had imposed on so many. What will your step be?

If my father were still alive, he’d encourage you to stand up and fight. He’s not here, so I’m doing it for him. Civil rights aren’t about “way back then.” They’re about right now. Civil rights also aren’t about “some people.” They’re about—and for—all people.

Staff Writer; Sharon Bennett

May visit this sister online over at; http://www.SharonKBennett.com.

Also reach her via email at; SharonBennettJ@Gmail.com or cell phone; 888-321-9604.

Leave a Reply