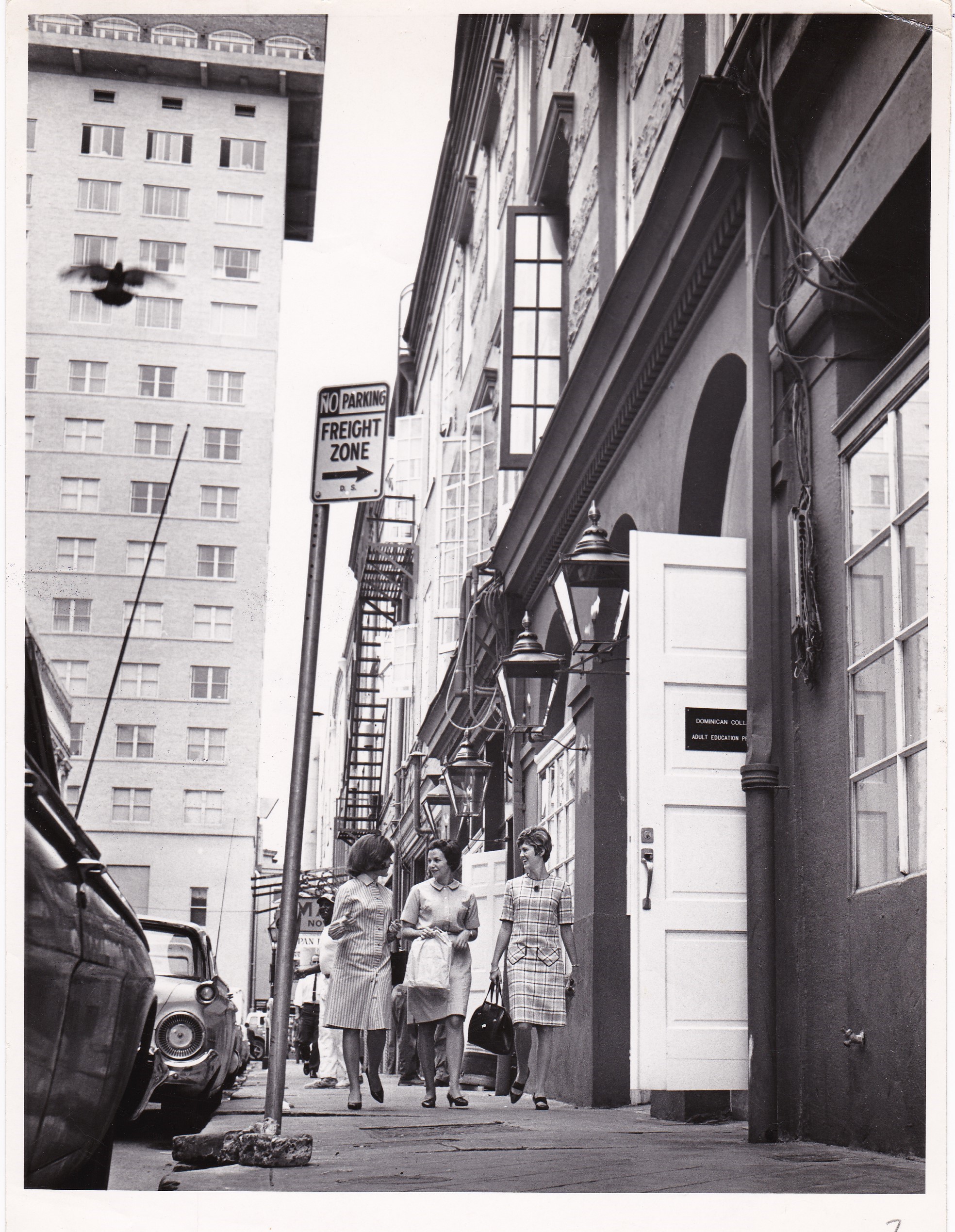

In 1965, on a seedy street in the New Orleans French Quarter called

Exchange Place,

in a space that formerly housed several rough bars and illegal gambling joints, an experimental school began that would change the moral skyline of the Deep South’s largest city.

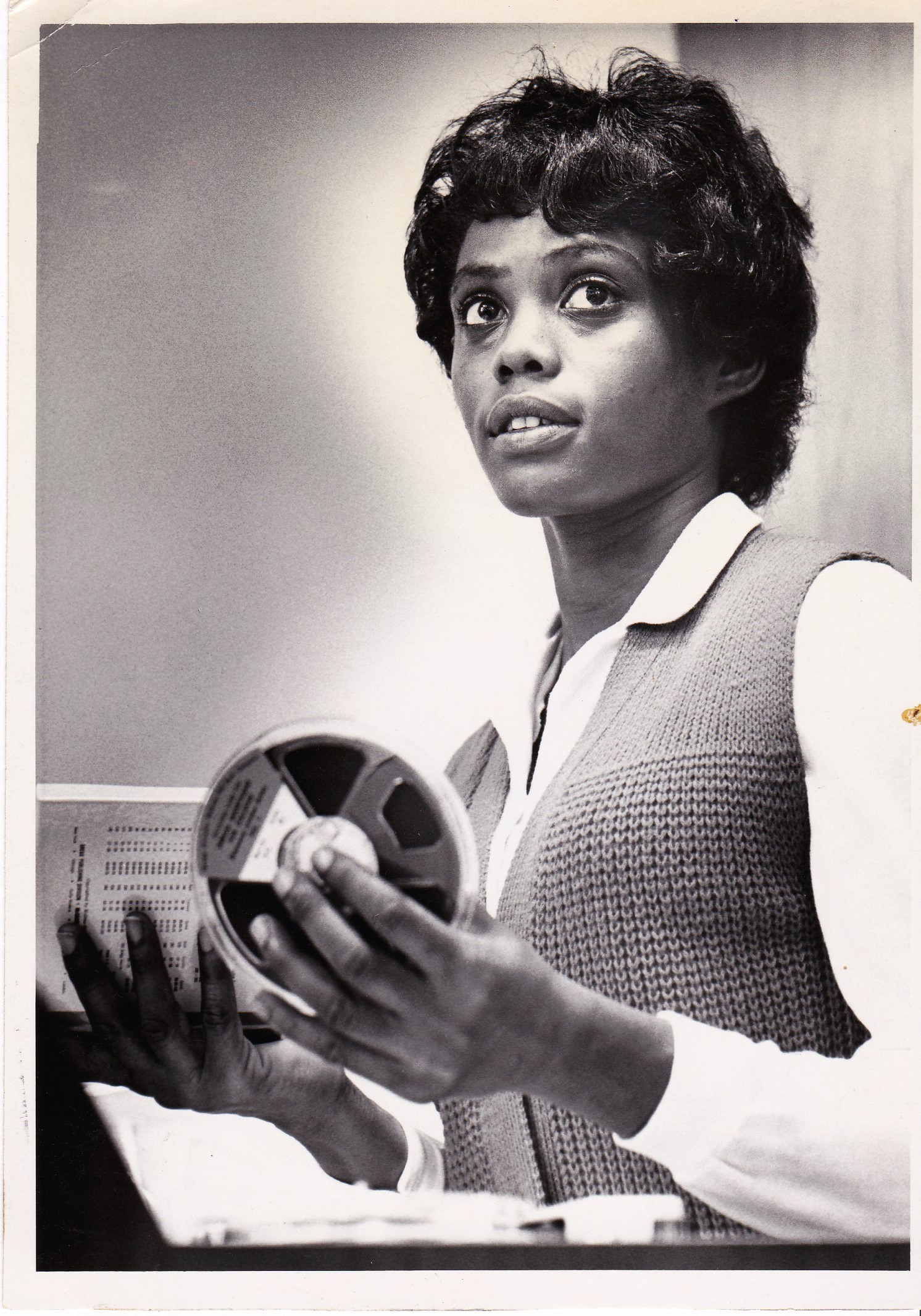

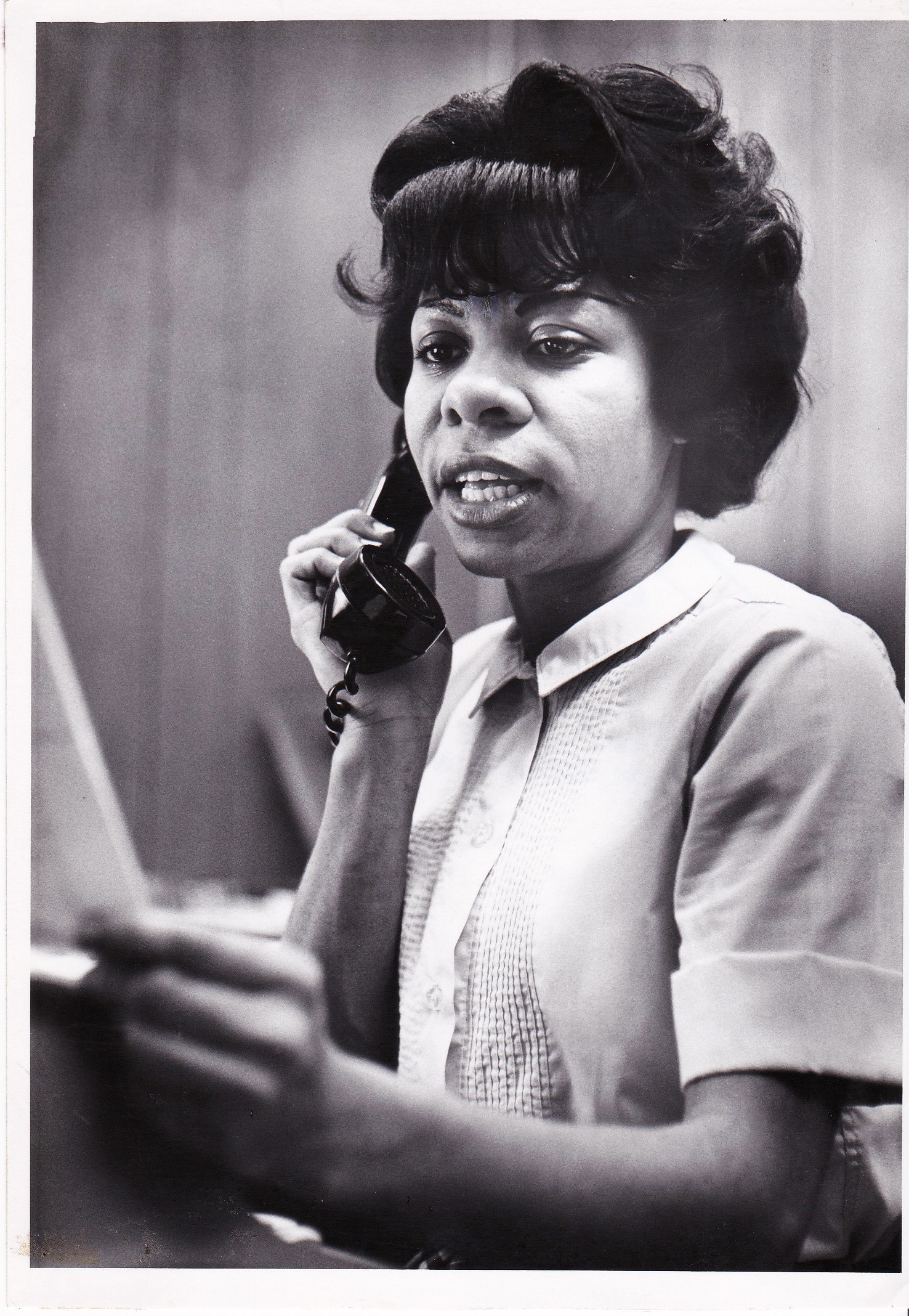

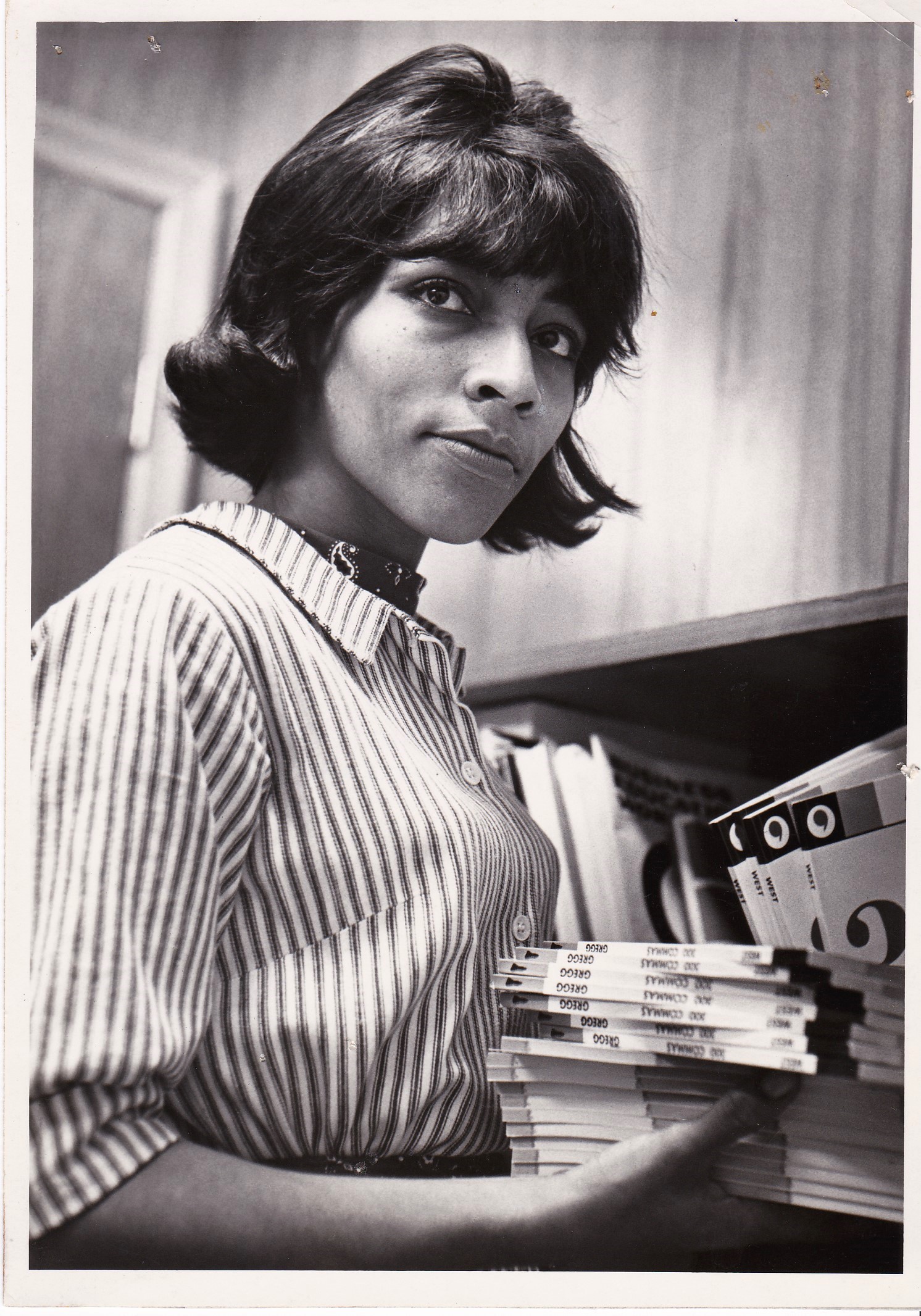

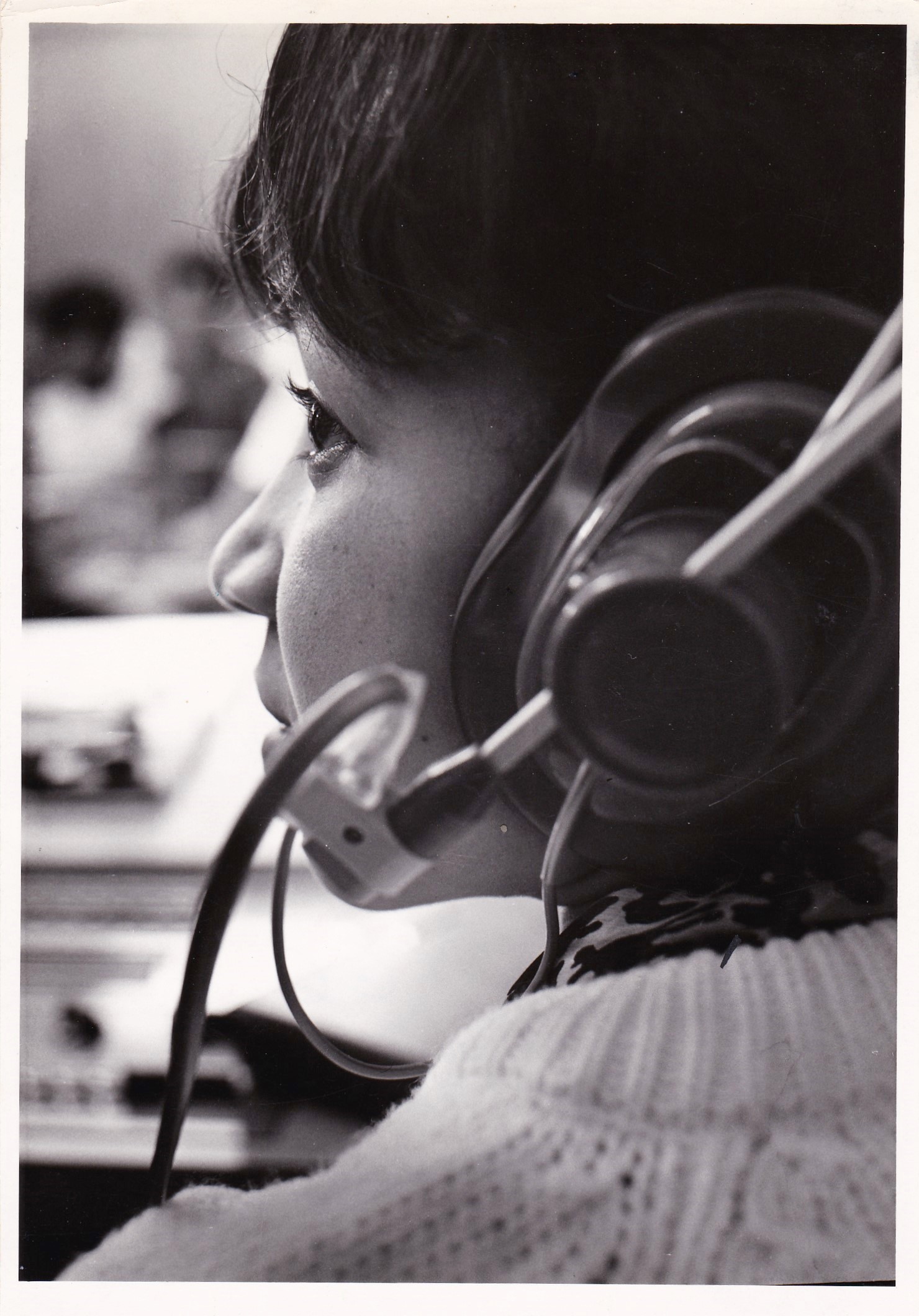

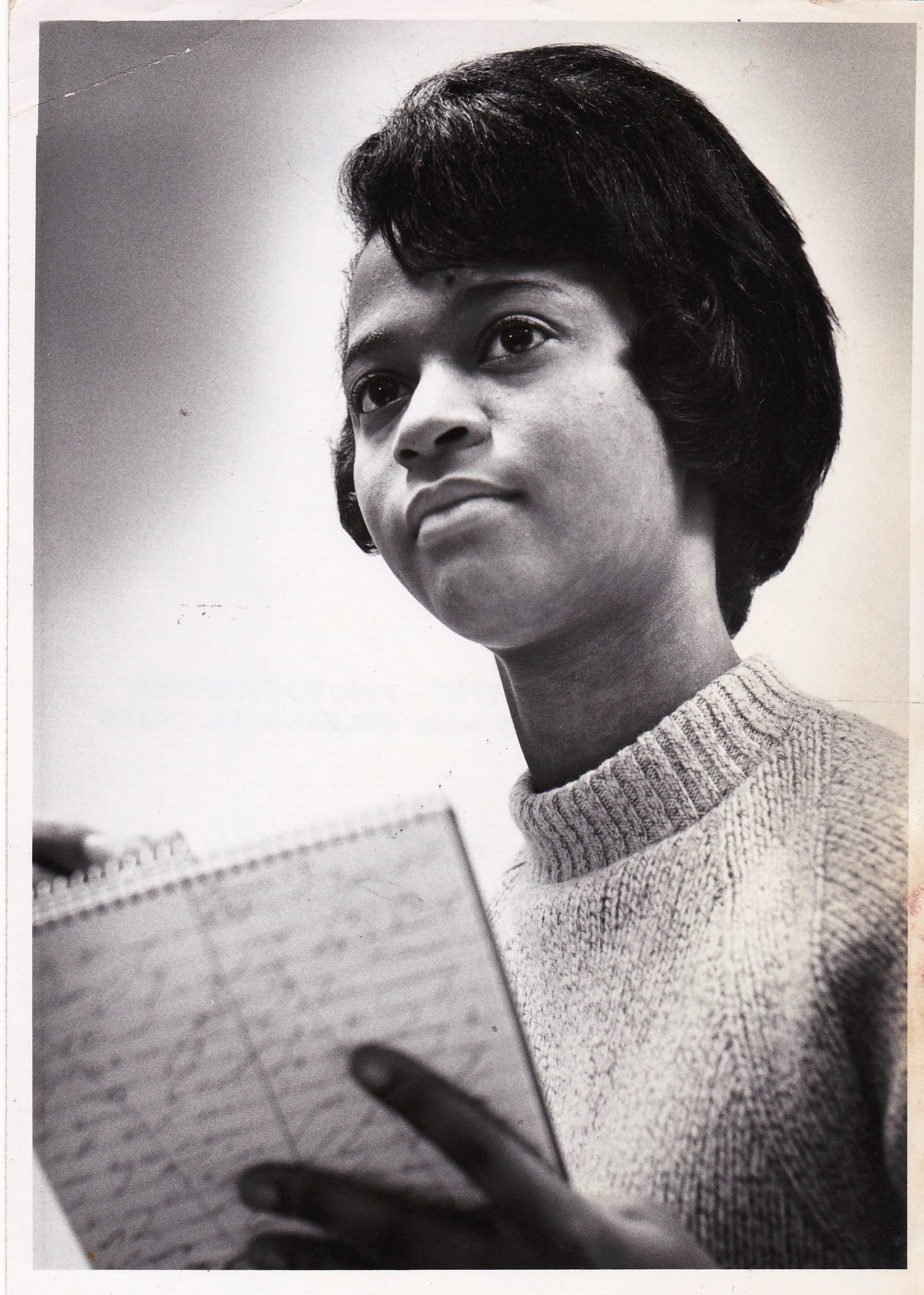

The students of the school, known as the Adult Education Center,

were underemployed mostly African American women who would become the first secretaries to integrate the city’s businesses at a time when 100% of its companies were segregated.

The goal of the school’s founders was so controversial that the first class was shut down when white residents of the community objected to Black women attending a school in their neighborhood. In search of a new location, 60 landlords refused to rent them a space. Finally, one brave landlord, James Coleman, Sr., offered them a home.

This is the story of the super-women who graduate from the school, and their teachers, whose joint-mission to achieve success while overcoming the forces aligned against them would be as unlikely an achievement as landing a man on the moon.

![[From left] Brenda, Eunice, Carol and Pamela Cole, four sisters who were all graduates of the Adult Education Center, are recognized with letters of commendation by Charles Blackburn, Vice President of Shell Oil Co.Photography by Leon Trice](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ab2a8423917eee8847d15c4/1572496113907-ZAFA922FV3WWO34PXDID/Cole+sisters+-+Leon+Trice+Photography.jpg)