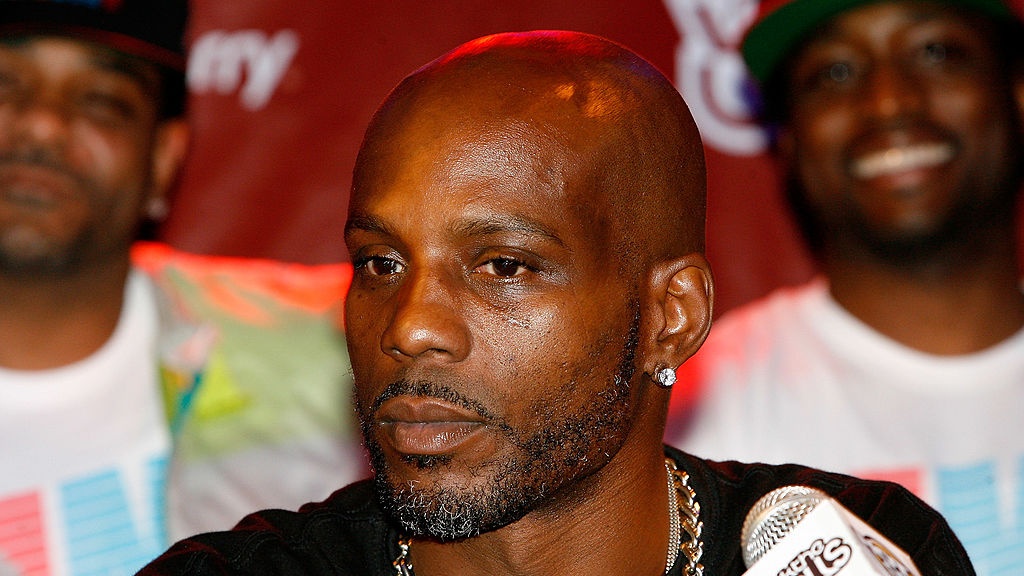

DMX, one of the most successful rap artists of all time, died Friday at the age of 50. The rapper, born Earl Simmons, was one of the most iconic hip hop artists of the 1990s. From the one-two punch that was his debut album It’s Dark and Hell is Hot and his follow-up Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood to the top of the Billboard charts in 1998, DMX’s pit bull persona provided a perfect metaphor for the way he sunk his teeth into rap and pop culture and refused to let go.

By the time of the late 1990s post-gangsta rap era, a tough exterior was practically a requirement for mainstream rappers. Most major rappers projected an air of controlled danger – the Blood or Crip-affiliated street gangster, the corner dope pusher, the drug kingpin or pseudo-Mafioso made man. But DMX was a completely different type of dangerous: the guy you crossed the street to avoid at night and avoided making eye contact with lest you catch a brick (the blunt object, not the drug package) flying in your direction.

The contrast was even more stark when compared to the “shiny suit” aesthetic that had been adopted by P. Diddy’s Bad Boy roster and which had spread to other top artists. Having established their street credibility with their debuts, artists like Biggie, JAY-Z, Nas and more used the shimmering, oversized outfits and neon-infused videos to soften their images just enough for mass appeal.

Then came DMX, backed by dudes wildin’ on motorcycles and four-wheelers, wearing baggy jeans and bandanas, barking and growling as loudly as the chained dogs he brought with him.

At a moment when everyone in New York was trying to adopt the mantle of the recently-deceased Notorious B.I.G. (the fantasy Biggie of Life After Death, not the grounded thuggery of Ready to Die) and Tupac Shakur, DMX was in his own lane. And while certainly not a carbon-copy of the philosopher-thug that was Tupac, one could have found in DMX a sort of spiritual successor – an unrepentant street dude who often wore no shirt but wore his heart on his sleeve. Like Pac, he had range — he could tell a story of robbing guys in one song and the tale of a strained romantic relationship running its course in the next, and both rang equally true.

I was 16 when DMX’s first album came out, and had just turned 17 when his follow-up dropped.

I was a casual hip-hop fan, but much closer to a church kid than a thug (which, at the time, was the epitome of coolness). My folks weren’t prudes, but I knew enough not to play the unedited versions of popular songs within earshot of my aunts or my grandmother. But when it came to DMX, he wasn’t just cussin.’ He was talking about murder and mayhem, literally talking to God and the devil on different tracks, bragging about necrophilia (no, really, see for yourself – very NSFW). His menacing picture on the first album cover was one-upped by a photo of the man dripping in blood on the front of the second album.

Though basically every popular rapper was threatening to shoot you if you crossed them, DMX claimed he would rip out your heart, brutalize your kids and defile your corpse. Though some of the content has not aged well, the dark, violent, horrorcore-inspired imagery prefaced later artists like Eminem or Tyler the Creator who would make careers out of saying horrifying and off-the-wall-stuff. And while these later artists hardly hid the fact that their shtick was meant to gain publicity and album sales, DMX sold it with a straight face – this dude might genuinely be out of his mind.

But there was a method to DMX’s madness. Much like how the Wu-Tang Clan’s Ol’ Dirty Bastard cleverly presented a complex artistry disguised as drunken rambling, DMX carefully crafted his artistry while putting it underneath the veneer of erratic aggression. Listen to songs like “Stop Being Greedy” or “Damien” as DMX modulates his voice to convey inner turmoil or the devilish influence of his dark side.

With a lesser artist, this kind of thing would come off as corny or gimmicky. For 16-year-old me, and for millions of fans who lapped up his albums, it felt like a magnified dramatization of real internal conflict. And while the barely-suppressed rage was part of it, so was the spirituality. The prayers and conversations with God, which became mainstays of his albums, seemed no less affected than the darker stuff. Even though the other 90% of what he was rapping about was fairly unholy, Simmons felt like he was genuinely seeking God, and the prayers were glimpses into a troubled but hopeful soul, trying to find redemption and purpose in the midst of a grimy world.

The fun thing about DMX, though, was that he didn’t just target you with his infectiously chaotic energy but let you inside; by listening to his music and rapping along, you could be the pit bull. Put on “Ruff Ryders Anthem” or “Party Up (Up in Here)” today in any setting – a party, a long drive, a Friday afternoon at the office – and the whole place is guaranteed to get hype.

It doesn’t matter that he’s throwing graphic insults and threatening retribution against his enemies – hopefully not something that generally happens at your place of work – because the enthusiasm and aggression that he brings to the tracks will be relevant to something going on in your life, and barking along to DMX will give you the motivation to tackle the grievances within your own life.

Earl Simmons always seemed aware of the charisma that he presented. Even when his story went from success to cautionary tale, there was always something there, despite all the arrests and drug relapses. At his worst, he was a man trying but failing to get it together, having more spectacular and more public failures than most of us but "Slippin'" in ways that were at least somewhat familiar, even if the details were not the same.

At his best, he was an inspirational figure who, through his success and his dominating personality, made you want to be like him. When those kids at the end of the “Who We Be” video, declare “I am DMX” in a nod to Spike Lee’s Malcolm X, it’s not hard to imagine that, in another life, Earl Simmons could have been the type of leader and inspiration that Malcolm was in his lifetime.

So while it was the rawness and the energy that made us like DMX, it was the unrealized potential and the constant struggling we watched him endure that made so many of his fans love him.