A New York City historian is fighting to preserve a school building whose past is tied to a dark moment in American history.

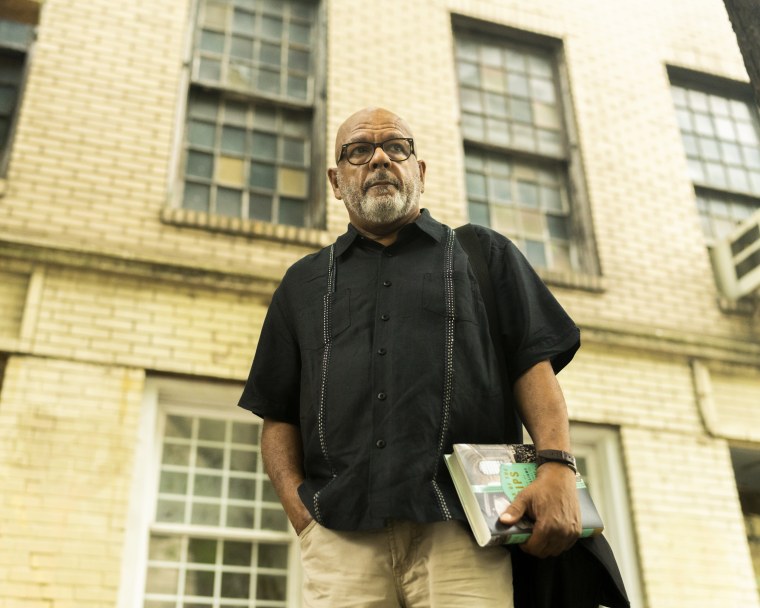

Eric K. Washington has been working for more than four years to preserve Colored School No. 4, one of the few remaining school buildings created for Black children during the slavery era, and later during segregation, in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood.

And now, after years of work, his efforts are gaining support from others calling to preserve the historic building.

According to Washington, the school served as a safe space for Black students during the New York Draft Riots in 1863, when working-class white men across New York City protested new laws passed by Congress mandating their service in the Civil War.

These protests are still among the most deadly instances of racial violence in urban American history. Local newspapers reported the death toll at 119 after white rioters targeted and lynched Black New Yorkers, though historians have estimated that the actual number of people killed may have been as high as 1,200. It was during these horrific riots that a white mob congregated in front of Colored School No. 4 while the school was in session.

Black suffragist Sarah J. Garnet, the school's principal, prompted the teachers to barricade the front doors leading to the streets. After a few attempts to break in, the rioters turned their attention elsewhere and the schoolhouse survived, unscathed.

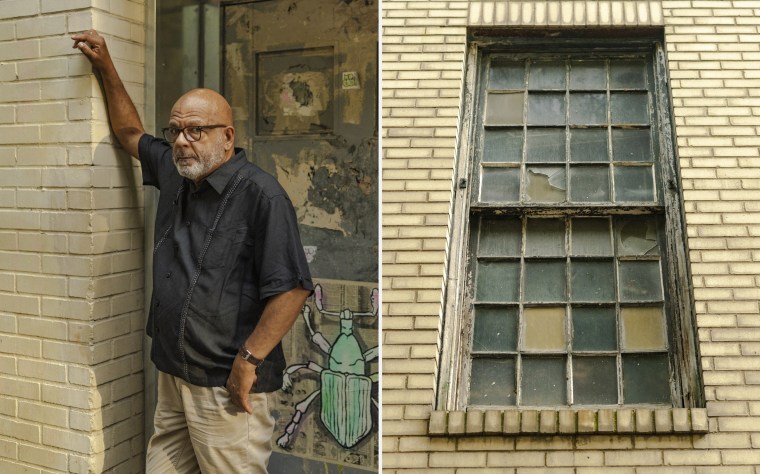

The school still stands 159 years later, but after a heavy toll: Its doors are laden with dust and its exterior walls are covered in graffiti.

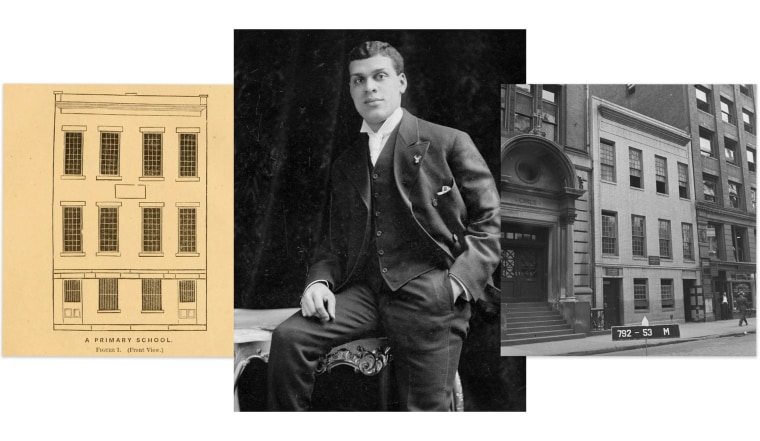

Washington first learned about the school when writing his book, “Boss of the Grips,” on the life of James H. Williams, the first Black chief red cap, or train porter, of Grand Central Terminal in the 1930s.

“Williams graduated from the school, and it sparked my interest when I realized the building is still here in Chelsea,” Washington said.

In his book, Washington describes the school as a “three-story, beige bricked building that once protected hundreds of Black children” and was an “important refuge for Black New Yorkers after the Civil War.” He also notes that the building evolved into a bustling community center for the African American working class.

In November 2018, Washington filed a request for evaluation with the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission to obtain official landmark status for former Colored School No. 4. After four years of little response from the agency, Washington is now running a grassroots campaign, hosting public “lunch and learn” events on Zoom, and gathering signatures for a petition to designate the building a landmark.

“It is crucial to create this touchpoint of African American history in widely gentrified Chelsea, which is a tourist area in New York City, and in the world,” said Thomas Lunke, a long-time Chelsea resident and an urban planner, who has been advising Washington in his quest to landmark former Colored School No. 4.

Few sites across the 37,000 places across New York City’s five boroughs with landmark protection are related to the Underground Railroad or antebellum Black history. Now, historians like Washington and others are attempting to preserve any remaining sites that have withstood development, destruction or neglect, despite critics of such landmarking attempts casting these buildings as unimportant or substandard.

The city's Landmarks Preservation Commission, which oversees local preservation, told NBC News, “Our research is sometimes informed by requests from the public which could include local community boards or Council members who may suggest a potential landmark.”

Manhattan Community Board 4, which represents Chelsea, facilitated a meeting with Washington and the Department of Sanitation, which currently owns the building. Following the meeting the Department of Sanitation said in an email that it supports “the landmarking of this property to highlight and preserve its significance in New York City history.”

New York City Council Member Erik Bottcher, whose district includes Chelsea, also wrote to the Landmark Preservation Commission to designate the school building a landmark. Multiple local organizations and a nearby co-op board have also submitted letters in support of officially preserving the building.

Recently the commission told NBC News that it has “decided to prioritize further research of former Colored School No. 4.”

As a result, Washington said he felt "optimistic" with the latest developments.

If the site is landmarked, it can be used to memorialize the rich Black history of New York City.

“The ideal outcome of landmarking the schoolhouse would be turning it into a museum or lyceum of sorts, so people, especially tourists, could learn about the trajectory of African American experiences,” Washington said.

Preserving this school building, however, was not Washington's first attempt at landmarking. In 2020, for example, he was part of a group that presented historical records attempting to show a property on Riverside Drive may have been used as a stop on the Underground Railroad.

The Landmarks Commission swiftly rejected the proposal, stating that the property “retains neither the historic appearance nor adequate historic fabric from the 19th century abolitionist era.”

Historical documents directly proving stops on the Underground Railroad are hard to come by, as these structures operated furtively, in fear of white slave owners discovering them.

“If there were more African Americans in positions of such decision-making, these unique sensibilities and sensitivities regarding African American history would’ve been accounted for,” Washington said.

To preserve a site under the National Historical Preservations Act of 1966, a site must either be architecturally, historically or culturally significant. But Washington and Brent Leggs, senior vice president of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, said the criteria can be arbitrary and biased toward white or European-centered historical sites.

Meanwhile, Colored School No. 3, in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, has been a landmark since 1998. The difference lies in the architecture. Colored School No. 3 was redesigned in 1879, by Samuel B. Leonard, into a Romanesque style, a one-and-a-half-story red brick building, emulating colonial, Eurocentric architecture.

Washington views the “architectural significance” criteria as a “systemically racist practice.” Buildings that represent Black history, like slave cabins and colored schoolhouses, are often unostentatious, and instead offer evidence of oppression of Black people by their white counterparts.

Leggs said, though, that the importance of preserving a site like Colored School No. 4 is finding ways to recognize Black Americans’ preservation and agency, instead of being victims of oppression.

“One of the challenges we face in preserving African American historical sites is expanding the historical understanding beyond the stereotype of racial violence with agency for the Black community,” Leggs said. “But that is most important in confronting America’s past.”