Commodity. Chattel. Contraband. Capital. What is a Black body in the South? What is a Black southern man, carted out to work a white-owned field?

It’s impossible today to talk about Black men and white agendas without talking about Herschel Walker, the Republican candidate for Senate in the runoff election in Georgia. But in order to talk about Walker, I’ve got to start in what may be his actual state of residence, Texas.

I watched the film version of Friday Night Lights almost obsessively during my senior year of high school. My father had just died. He was a diplomat, a businessman, and the general counsel of the U.S. Army, and he loved conservative optics and southern spaces and all manner of iconic Americana, for good or ill. So the movie connected me to him, or something—offered me catharsis, or something. The movie immersed me in all of the hard, strange things about the South, the questions about achievement and race and class and excellence and objectification, and what it can mean to lose or win or talk to God about any of it.

But there was one scene I hated to watch.

Coach Gaines is getting ready for the start of the season, and attending a booster-club dinner with a table of wealthy white donors who presumably love God and football and Texas and not a whole lot else. It’s a subtle scene, the dinner party spliced with distracting clips of the players at a raucous high-school party. A woman talks almost salaciously about the physicality of the young men she saw on the field during practice: “What I saw was speed out there, but where’s the beef, Coach? I saw me some small boys.” The master’s wife, perusing the auction block. Then a cut to more beer guzzling, more Run-D.M.C., more teenage hijinks. And then it’s back to the elegant, sinister dining room.

Quietly, the woman worried about how small the players are this year offers Gaines some advice. “You know what you should do?” she says. “You should play Boobie Miles [on] defense. Work him both ways.”

Coach doesn’t quite see it that way—you don’t risk your prize thoroughbred on a recreational outing. “Well, see, the problem with that is,” he replies, “I don’t want to get him hurt. We need him to score touchdowns.”

The woman doesn’t miss a beat. And her reply is seared forever on my brain. “Bullshit. That big nigger ain’t gonna break. You wanna beat Midland Lee, you play him middle linebacker.”

That big nigger ain’t gonna break. Every time I watch one of these smug, jowly, dangerous Republicans sitting next to Herschel Walker, wheeling him out for their own designs, I see that dinner-table conversation in the background of my mind. Walker is a big, ball-carrying Black man, and these Republicans do not have an ounce of care for him. They are using him to advance their own Constitution-compromising agenda, the way conservative white people in this country have always used Black bodies when given half a chance.

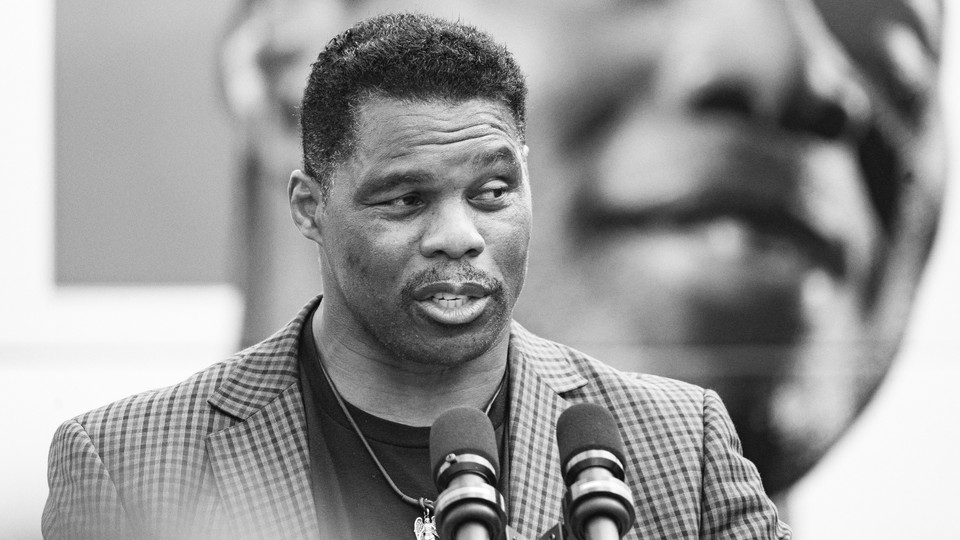

Walker stands up at podiums, and I feel shame and sorrow and resentment. He is incoherent, bumbling, oily. He smiles with a swagger that does nothing to disguise his total ignorance of how blatantly he is being taken advantage of by a party that has never intended to serve people who look like him.

Walker’s candidacy is a fundamental assault by the Republican Party on the dignity of Black Americans. How dare they so cynically use this buffoon as a shield for their obvious failings to meet the needs and expectations of Black voters? They hold him up and say, “See, our voters don’t mind his race. We’re not a racist party. We have Black people on our side too.” Parading Walker at rallies like some kind of blue-ribbon livestock does not mean you have Black people on your side. What it means is that you are promoting a charlatan—a man morally and intellectually bereft enough, blithely egomaniacal enough, to sing and dance on the world stage against his own best interest. Is he in on the joke? Does he know they picked him to save money on boot black and burnt cork, this man who made his name by bringing the master glory on the master’s field, who got comfortable eating from the master’s table?

For the record, Coach Gaines did play Boobie Miles, and Boobie Miles suffered a career-ending injury. And the team carried on. They left him and his broken Black body behind. His dreams, nothing to them. His legacy, utterly compromised.

Whether Walker wins or loses, whatever was good or valuable or worthy about his prior professional legacy has been utterly compromised. His many trophies are now and forever eclipsed by the humiliating spectacle of his political foray. He is ruined, and the party that propped him up does not care.

From where I sit, the election looks like a kind of grotesque minstrelsy. The Republican Party is saying that it wants power more than decency. It’s saying that race is a joke. We must all take note—it is willing to destroy a man to advance its cause. The party thinks he won’t break. And if he does, well, he wasn’t really one of them, anyway, was he?

I grew up in Tennessee and still live here. Although it has become obscure, in the South, if you listen closely in the right (wrong) crowd, you will still hear the term ofe thrown around to describe a Black person. Not o-a-f. Ofe, spelled o-f-e. Obsolete Farm Equipment.

I’ll ask again: What does it mean to be a Black man in the South, working a white-owned field?

I don’t particularly care that Herschel Walker doesn’t seem to know he’s being used. I care that America let it get this far, that this country has been wildly careless with Black bodies, Black stories, Black truths. I care that I’m watching the news every day with the foot of bigotry on my back and the noose of regression tightening around my throat.

Whoever wins today, Walker’s candidacy is an American tragedy.